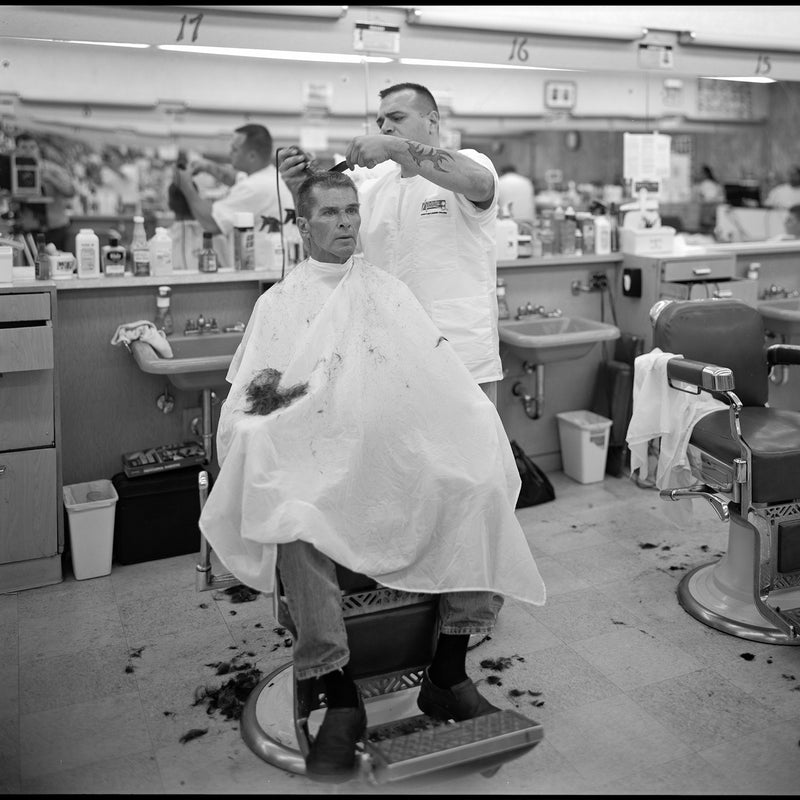

Tamrin Ingram, telling the stories of rural America

"I grew up on a gravel road alongside the Spanish moss and the cottonmouth snakes in Northeastern Louisiana. I come from a rural community of pipeliners and I spent the first years of my life travelling with my family as my dad worked job to job across the United States. I was raised on a steady diet of tall tales, adventure stories and country music which is probably what instilled my passion for storytelling and travelling. When I was a kid, my mother passed away unexpectedly and eventually my family moved to Ohio where I went to high school and then received my BFA at Columbus College of Art and Design in Columbus, Ohio. The Midwest never felt quite like home and as soon as I got the chance I left Ohio and moved to Tucson, Arizona where I am about to go into my final year of the MFA program at the University of Arizona."

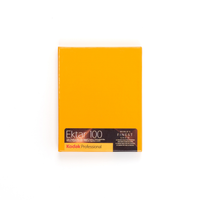

"Despite all of my moving around home has always been a gravel road in Louisiana, and all of my work is still centred around the rural community that I come from. At my core, I am a storyteller. Within my artistic practice, I layer my writing, photographs and family records to construct narratives that play between fact and fiction or history and myth. In previous projects, a family curse serves as the hypothetical root cause of generational trauma. The disproportionate illnesses and untimely deaths that have historically plagued my extended family don’t have a rational origin. It doesn’t pinpoint what is really to blame. The curse is a metaphor for our position in an area overcome with cancer rates and other illnesses, some of which stem from rural pesticide pollution and lack of access to quality healthcare.

This summer I’m starting a project photographing Superfund sites in Louisiana. In 1980, the United States Congress enacted the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) to address the threat of hazardous waste buildup at concentrated locations. CERCLA established rules for hazardous sites it identified as a threat to the environment or public health, then determined the responsible party to comply with the regulated clean-up while holding them accountable for its funding. Sites managed under this program are called Superfund sites. After years of improper management of hazardous wastes and their removal, as well as unsafe resource extraction, Louisiana has become one of the most polluted states in the country."

Family and past family trauma is a big part of your work so far, do you think the upbringing you had was a core influence in your desire to take photos and create art in general?

"I have very early memories of looking at old family photo albums with my dad, he would tell me the names of the people in the photos and they would all come equipped with stories about who they were and what they were like. I don’t know if it was the stories that I loved so much or just looking at the old black-and-white photos of people I’d never met and places I’d never been but I felt a very strong attachment to them all. Then later on when I got my first 35mm camera I knew that I had to take pictures of everything because I was afraid of forgetting the little details. I wanted to remember everything about being a kid and I wanted to have tons of photo albums so that someone could look back and tell my stories. Of course, at the time I never realised that this could all be ‘art’, I didn’t even know what art was (or I guess what it could be) until I got to college, but that was definitely the beginning of it all for me."

You mentioned your latest project focuses on ‘Superfund sites’ in Louisiana. Do you feel a sense of justice to raise awareness on the issues surrounding these sites and the impact that the government's failure to manage them has had on local communities?

"Yes and no. I don’t consider myself an activist, maybe that’s an uncool statement in the contemporary art scene but it’s not a label that I’ve branded myself with. I want to tell the stories of these places and yes I do want to bring attention to what’s going on but I want the project to have other layers outside of the traditional documentarian nature of raising awareness. Louisiana’s nickname is ‘Sportsman’s Paradise’ and I want to investigate the theme of paradise and pull that into the work as well. I’m always looking for a way to incorporate elements of myth into my work and I love toeing the line between fact and fantasy, something that comes out very naturally in my written work but I’ve got to work a little harder to figure out how to push it forward in my photographs."

You merge creative writing with photography in your work. Did you start out doing one more than the other, or have you always felt compelled to combine your creative outlets?

"It’s definitely been only a recent thing to combine them both, and I’m still not convinced that I’ve found the most successful way to combine them. I started taking pictures when I was six years old. I had a small 35mm camera that I got in my Easter basket one year and from that moment on I was never far from a camera. But it was never art back then and I didn’t even realise it was a creative outlet, it was just something I did all the time. Writing, however, was always a creative outlet and I had wanted to be a writer from a very young age but by my senior year of high school something flipped and I decided pretty late in the game to go to art school instead of going to school for writing or literature and it wasn’t until my senior year of undergrad that I started writing again and incorporating text into my artwork. Now I can’t imagine not utilising both mediums, but like I said I’m still working on perfecting how to combine them."

Do you find creating the work you do has helped you explore deeper into your past and the locations that surround you?

"Absolutely. A lot of my inspiration comes from stories I’ve grown up hearing about and old family photos I’ve grown up looking at, so I’m always asking questions and digging deeper into my family's past, always trying to piece together the history. I’m obsessed with multigenerational connectedness and how a family communicates with past generations, whether it be through storytelling or looking at old photographs or even using old family recipes at the dinner table.

It’s a similar thing with the landscape around where I’m from too. I’ve been trying to investigate the land with a much more critical eye, trying to learn the history of locations to see how those histories affect the populations living there today.

There’s a quote from Sally Mann’s memoir ‘Hold Still’ that I feel sums up a lot of my ideas as an artist and hits on the topic of connecting with the past. She says “Southern artists, and especially writers, have long been known for their susceptibility to myth and their obsession with place, family, death, and the past. Many of us appear inescapably preoccupied with our historical predicament and uniqueness, which, as the Southern novelist Andrew Lytle once remarked, we can no longer escape than a Renaissance painter could avoid painting the Virgin Mary.”

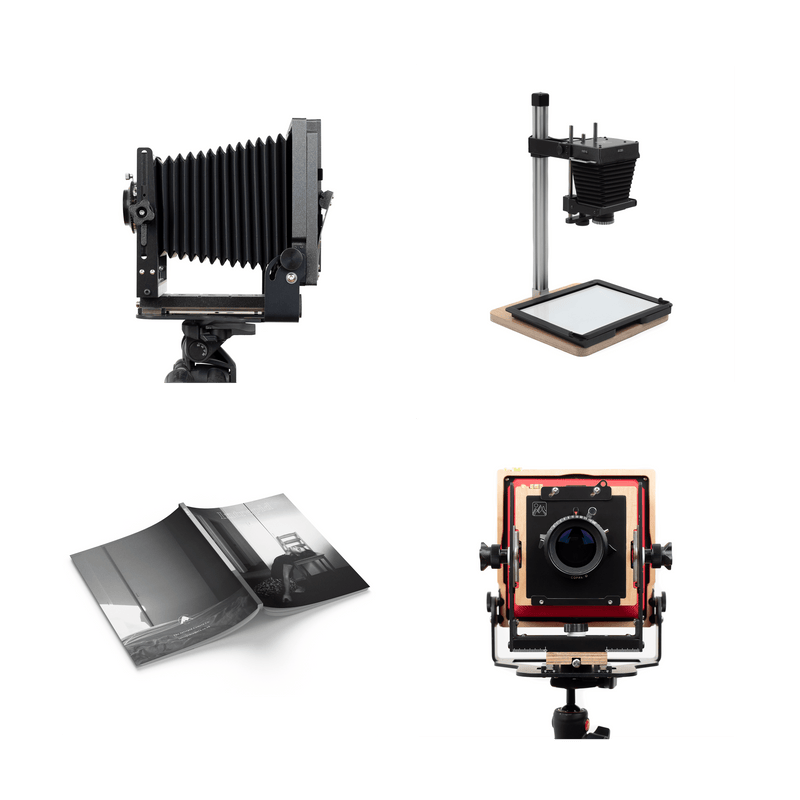

Do you feel using film added something to this work that perhaps would have been harder to achieve with digital?

"I’m a very hands-on maker, so I’m naturally drawn to the workflow of analogue processes, and my reasons for choosing film all comes down to the physicality and slowness of shooting film. I feel like I need the time it takes to set up my shots with a large format camera, the methodical nature of it gives my brain the time and space to process what I’m seeing and how I’m seeing it. I’m naturally a slow worker with most things so it’s a very natural way of shooting for me. And working in the darkroom to develop film gives me time to really think through my conceptual framework. I’m also still a sucker for the magic of shooting film and the feeling of turning the light on and holding up a piece of film to the light to see if an image is on it will always be one of my favourite feelings. Aesthetically film just feels better to me, I don’t dislike digital imagery but it’s a lot easier for me to get lost in the grain of an analogue image than to get sucked into a digital one."

How did you research and find the locations for Pointing at Nothin? Had you already planned the locations or did it take a lot of work beforehand?

"Pointing at Nothin came together somewhat organically but all of the locations were intentional. I’ve been obsessed with the idea of houses being these sort of ultimate family members, they’re the literal container of families that they help protect and raise. When my maternal grandmother passed away last fall I made several photographs in and around her house, the same house my mother grew up in, and the rest are from around the house that I grew up in, which is also where my dad grew up and has been abandoned since my mom died. I guess I view these two locations as my maternal and paternal origins, and I’m always going back and making more photographs both in the houses and around the property where the houses sit. I think there’s still more of a story to tell in these spaces."

Now that you live in Arizona, do you think you will stay and work on projects there also or do you plan to return to your roots?

"I love Arizona, and living out west is a dream come true. As a landscape photographer, I couldn’t pick anywhere better to be and living in the desert is such a strange but wonderful experience. Sometimes I wish that I could stay in Arizona forever but I know that my stories are in the south and once I finish school the plan is to relocate back to Louisiana."