Mat Marrash on his Journey into Large Format

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit.

Back when Mat Marrash was a senior in college, he had the chance to jet off to Japan as part of a school exchange program. Because his girlfriend was already there teaching English, he took the opportunity to extend his trip, buying a Canon Rebel and teaching himself to use it so that he was able to capture some memories. When he got back home, he had tens of thousands of RAW files to sift through and fell in love with processing images and figuring out how to use the camera. Eventually, he became student photographer at his school. "By the time I came up for air, I had six months to go in school and zero interest in anything I was studying,” Marrash says. “It was all photography.”

After that, he got a few gigs for commercial studios in Northwest Ohio, took on work freelancing for high school and college sports events, and started shadowing wedding photographers. But he’d also made it back to Japan for a couple more trips, and near the end of the second one, saw the huge appreciation in the country for film cameras and decided he needed to get one. It was around the time many people were ditching their medium format equipment for digital setups, and he was able to pick up a Hasselblad in May 2009. He brought it along to a wedding and told the couple that he’d shoot a few rolls on it to see what came of it, with no guarantee that anything would turn out. Not only did they turn out—the couple chose to build their wedding album entirely from those shots.

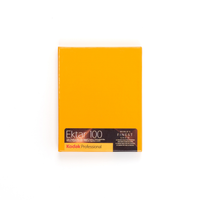

Since then, Marrash has dove deep into the world of film and especially large format photography, capturing the stunning and calm landscapes of his home state seen in his Hocking Hills and Ohio Uninterrupted series, and making his way through small-town America to shooting photographs for Barbershops, visiting over 140 shops in the process. When I caught up with Marrash late last year, he had just gotten back from a trip to West Africa.

So, what were you working on in West Africa?

"I had a project I was working on with a buddy of mine who's also a large format shooter, Tariq Tarey. He works with a lot of displaced people and immigrants, and I told him this year I wanted to do a little bit better with portraiture, and do some good with my camera, so we linked up with an NGO (Non-governmental organisation) over there and were doing some documentary work to hopefully raise some money for them."

What kind of portraits were you shooting?

"Environmental portraits of villagers who are helped out. The organisation we were helping out is called Andando and they support 70 different villages, which then in turn supports 21,000 people in rural Senegal. Senegal is one of the western most countries in Africa, and it's kind of the melting pot for a lot of the former French colonies in West Africa. So they have a booming population, but the folks out in the country have kind of been—I don't want to say 'left behind'—but there's a lot of advancement that's happening around there and the infrastructure isn't really doing them any favours. So this organisation comes in and provides resources, farmland, training, schools, the whole gamut, and they're a completely self-sustained organisation. They just need a little bit of support."

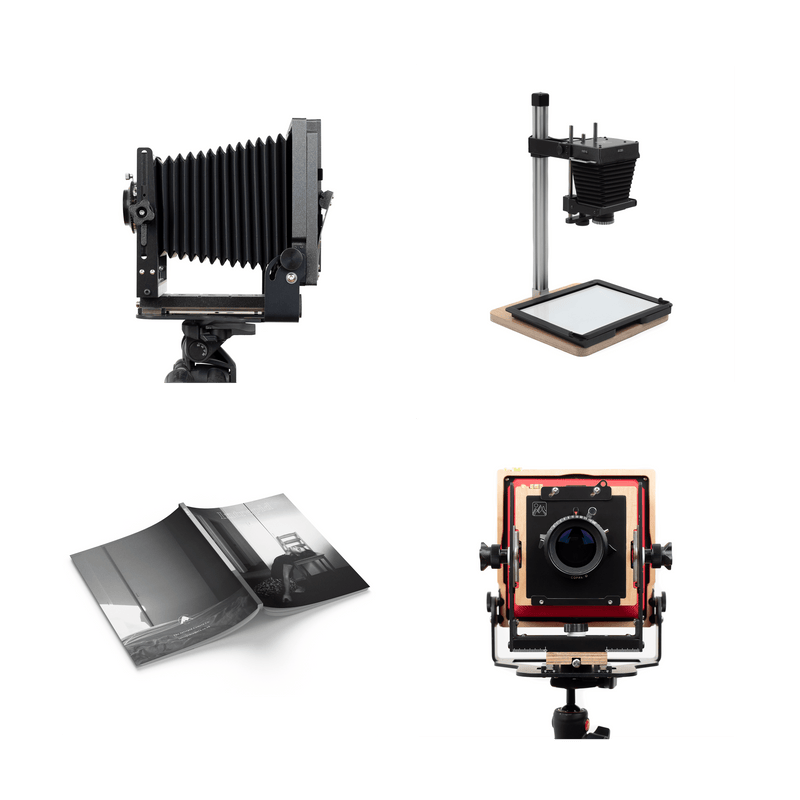

How did you get into large format photography?

"Once I had the Hasselblad, before that wedding spurred me into doing more film, I was like, 'I'm gonna shoot a roll of film a week, do like a 52 project thing.' So I was forcing myself to shoot at least one roll of film per week, and the same professor I had for my one official digital class in school, who also ran the darkroom at my college was like, 'you're really into this, aren't you?' and I said, 'Yeah!' I had a little bit of free time because I was rounding out the rest of my super senior year, at this point, and I just started printing more. He gave me access, and then one afternoon, I came in, and he was cleaning up this old view camera of his. It was an Eastman Commercial B, I was like 'what the hell is this thing?' He said, 'Oh, it's my camera, I was just cleaning it up because I was either gonna throw it out or sell it or something.' And I was like, 'No, you have to show me how to use this thing.' He said, 'I'll tell you what. Thanksgiving break is coming up. If you grab some film, I'll show you how to load it and shoot it and everything else.' So I overnighted some 8x10 film from Midwest Photo, where I work now, and was loading and shooting it the next day. That kind of bled into that 52 project, and I didn't look back. I just kept finding excuses to take this camera out. I really liked the process and the results."

What were the early challenges you had with large format?

"The biggest challenge was the time between shooting and realising what my mistakes were this time. Now there are a ton of videos out there. When I was getting started, there was maybe two or three good YouTube videos, and probably the best one that was out at the time was a re-upload of this old Calumet video. I jokingly repost it at least once or twice a year on my social media. Calumet had this old video for their Cadet series on large format photography. It was narrated by Bill Curtis, the same guy who's the narrator for Anchorman. A really famous Chicago announcer, because it's where Calumet was based. And it's just this tongue-in-cheek, really bad '80s instructional video. But it actually taught you a lot about how to use the camera, once you looked past the bad production value. So the biggest challenges were figuring out what I was doing with it, and realising that no matter how many times I read something or watched somebody else do it, if I didn't fail myself, I was just gonna do it anyway. So I could try to watch every technique video, but if I don't get out there and make the same mistakes, I'm just gonna make them anyway. I might as well get those mistakes out of the way. Then once I sparingly got new gear for the camera, I'd force myself to practice with it. I read a great article a long time ago from this photographer Bruce Barnbaum. His thing was to, once you have a new piece of gear, set it up a hundred times like you're going to take a picture, but then don't take a picture. So you know all the knobs and the ins and outs. Half of it is so you don't look like you're a complete newbie with it, but you can also just use it without thinking about it. That was super boring and a great waste of a day and a half. But I figured it out. Now it's like nothing. I love when I see videos where people are like, 'I've set up the camera and we've been out here for 45 minutes to an hour.' That is not my process. I'm up and shooting all within the first five minutes. If it takes longer than that, something's gone wrong."

That sounds like great advice. Most of the mistakes I've made with my Crown Graphic are due to overlooking steps in the process and set-up.

"They're just expensive mistakes where, if you do it once, you're like, 'great, that's an expensive mistake, I won't do it again.' And then when you do it another time, you're like, 'Shit, why am I doing this?' There's all this extra self-doubt that we don't like as photographers, but it happens."

Why do you still find it worth the trouble to lug the big camera around and spend the money on the film?

"I don't like to think of it like it's just an expenditure on a picture. If you look at it like that, everything we do is needlessly pointless and expensive. But the reason I like doing it is that there's enjoyment in the process for me, part of it is a workout plan. Lugging around 70 lbs worth of stuff is like... take that out once a week, hiking a mile or so, and you'll stay kind of trim. Then the amount you spend on film is kinda like a gym membership. It's really not that much more expensive than that $5 coffee a day or anything else. You're definitely shooting a little differently, but I still like it because I can see the world a little bit better when it's really abstracted—upside down and backwards. I really hate when I look at something head on, and then I try to see it like that through the camera. I know I'm missing something. If it's inverted on the ground glass, I'm looking for different things like shape, and I'm really attracted to different types of light, whether I'm shooting a camera like a camera or shooting something where I'm interacting with it, like a view camera. For me, there's a mental block. I'm trying to work over that, but it's not working. So I'll keep hauling around the big camera."

How do you think shooting in large format affects the way you visualise a photo?

"Oh, it doesn't completely remove the context, but it really breaks down light to its bare essentials. Here's your frame, you have complete control over it. If you don't like where it's falling, it's on you at that point. And it makes me realise that - I can't remember which street photographer said it, but our unique responsibility as photographers is for literally everything that's in the frame, and equally, what's not in the frame. When you're viewing it, coming in and out of the glass like that, it forces you to notice those little details. I'm going through a bunch of scans right now from Africa, and constantly forgetting little details, like, 'oh yeah, the light right back there, that's why I set the camera here and not over there.' It forces me to look a little bit harder. But at the end of the day, if you don't have the mechanics of that tool in the back of your mind, you're not going to get past that. I don't personally enjoy the whole attitude of, 'try this camera, try that camera, try this film on sale.' Really just get to know a couple of tools, that's really all you need. Get to know those incredibly well, and then you can start to play with the things that really matter in a photograph. Teaching classes, even for students who are shooting digital—that's part of my job at Midwest, I teach people who just got a DSLR how to use it—and everybody getting into it, we all have the same kind of idea. We all come from this really consumerist culture, so we can buy our way into certain levels of things. And it's my job to sit back and say, 'No, you have to practice with this, just like a band instrument, just like you practice writing. You have to practice all these things.' Teaching that constantly—I do this class at least once a week—helps to keep me telling myself I need to get out and practice too, and get out there and play around with it."

What are the logistical challenges of work like your Ohio, Uninterrupted? I assume you don't want to leave any sort of big footprint on nature while you're doing that.

"That's the great debate, right? Preservation vs. conservation. Having a biology background, specifically life sciences, I really respect nature, but at the same time I want to communicate that to other folks. Really, I didn't even start the project. A buddy of mine who works for Ohio Department of Natural Resources, I didn't even realise he was a Film Photography Podcast fan, until he came to me at work one day and said, 'I just listened to you on the Film Photography Podcast!' He'd heard I was bored of shooting Hocking Hills all the time, because I'd just finished photographing that every week for the last three years, and I wanted to look at other things. And he was like, 'You should come out with me, and we'll go to one of the preserves nearby, and I'll show you what you can do with that sort of thing.' And then he told me that there's a volunteer program, where if you volunteer for the state, and share a few images now and then, they'll give you access, which is basically the same privileges as a park ranger has. But you have to pack in, pack out, so it wasn't too different from the same way I normally shoot, but just really watching out for marked trails, don't eat anything, don't discard anything. It wasn't very hard, but it was an extra limitation, I guess. There wasn't as much off-trail. If you go off trail in Hocking Hills, they'll wag a finger at you. But if you go off trail in a place where there are five different protected plant species, some of the responsibility for losing one of those could be on you. Some other cool things happened during that project, like discovering whose interests were being served the most for that. There were a couple of preserves I went to where the only other folks I saw were across the street plotting out land for a fracking operation. In the 92+ preserves I visited, I only saw six people. One of them was a park ranger. So it was very meditative versus standard nature shooting, where you're getting up at the butt-crack of dawn or late in the evening, using an ND filter to remove people from a photo."

Especially with film, it seems if you don't spend enough time with specific types of it regularly, you never really learn how you can push the boundaries of them.

"Definitely. I don't want to seem like I'm a hypocrite—I'm on the Film Photography Podcast and I'm always talking about these great new things. I'm testing them, but I'm not doing like, work work with them. I'm playing around with them and it's casual. But at the end of the day, when I'm doing what I feel is the kind of work I want to produce, it's kind of falling back on those tools I know and following through the same sort of process. So very little actually changes. And I think after you go through dozens, hundreds, thousands of rolls of the same type of film, you'll also find your control over it shows you what your style looks like, and what the film can do. When you figure out those limits—if the limitation is you, or the limitation is the media—you can start to make those good compromises that produce your work."

What type of film would you say you have the closest relationship with?

"Because of my budget, Ilford. I've probably done way, way, way too much FP4 and HP5. Ilford, if you're listening, send me free film. They're the only folks who haven't yet! But I still buy their film because I respect what they do. I can never have a bad day shooting anything coming out of Kodak. Fujifilm I'll leave at a respectful 'no comment.' I don't think they care too much about anybody who isn't shooting Instax, sadly. But Ilford first and foremost, Kodak after that. There are other little guys sprinkled throughout there. If I could afford to, I'd shoot nothing but T-Max 400, but I would be well beyond homeless trying to shoot the same amount I shoot in Ilford. I think another thing that happens in large format is that you have this feeling of, 'I love this film in 35mm, what's it gonna look like in large format?' I find the differences kind of smooth themselves out once you have more surface area to communicate the same thing. In 35mm, I hate HP5. I don't like the look of it. But I love it in large format because two stops is everything when there's wind and depth of field issues and super long telephoto lenses. So there are some great things that the medium does, and the limitations of the medium do, too."

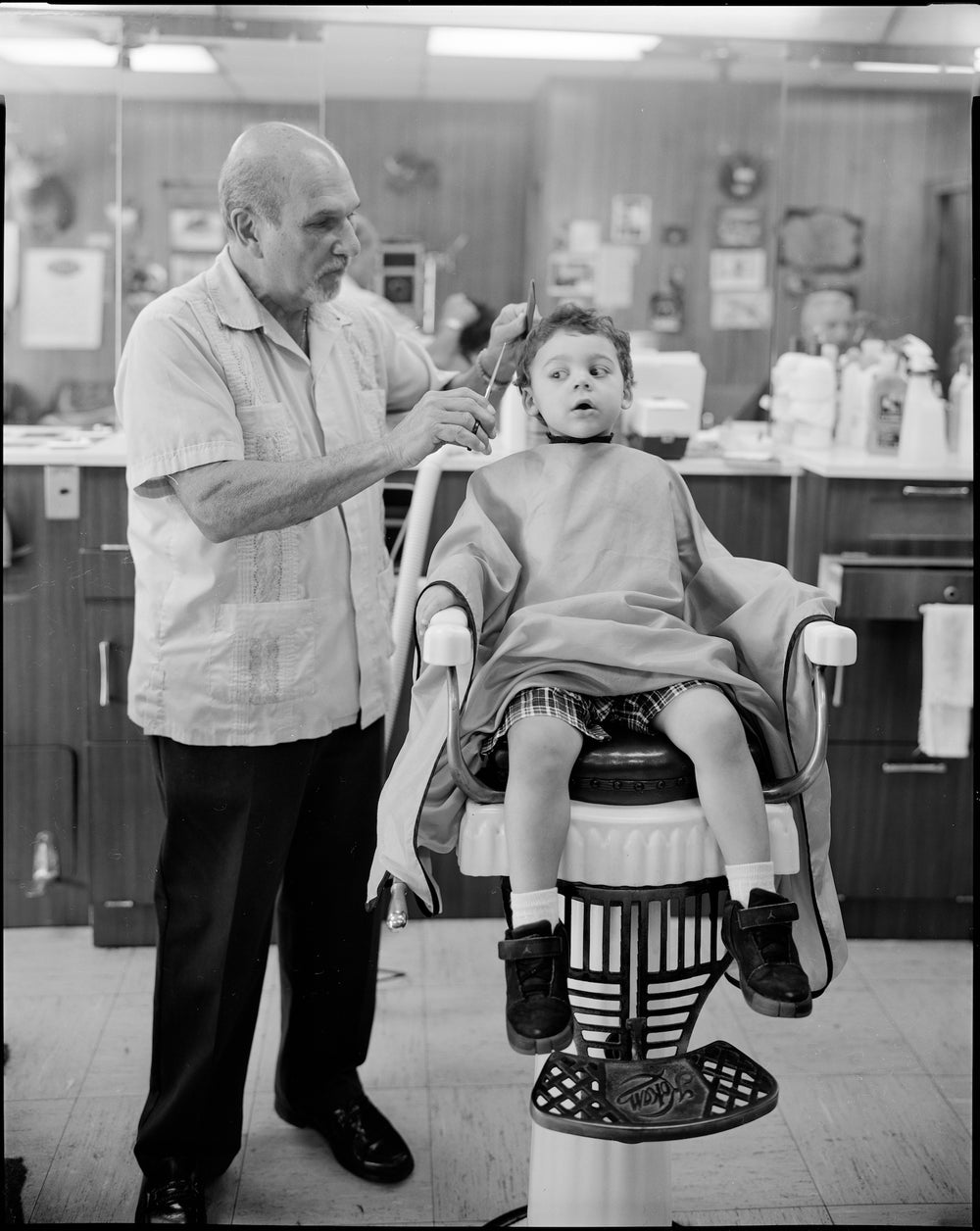

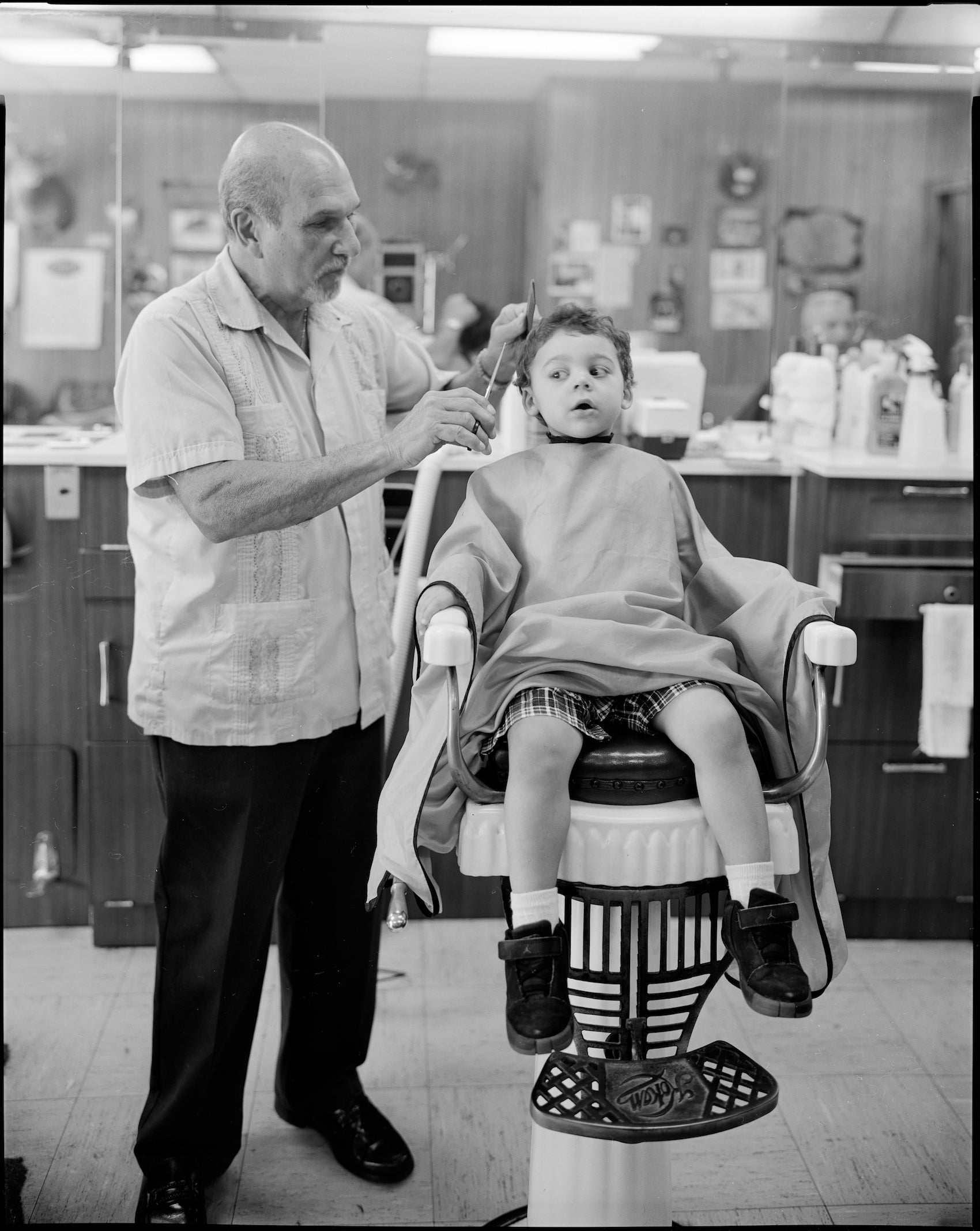

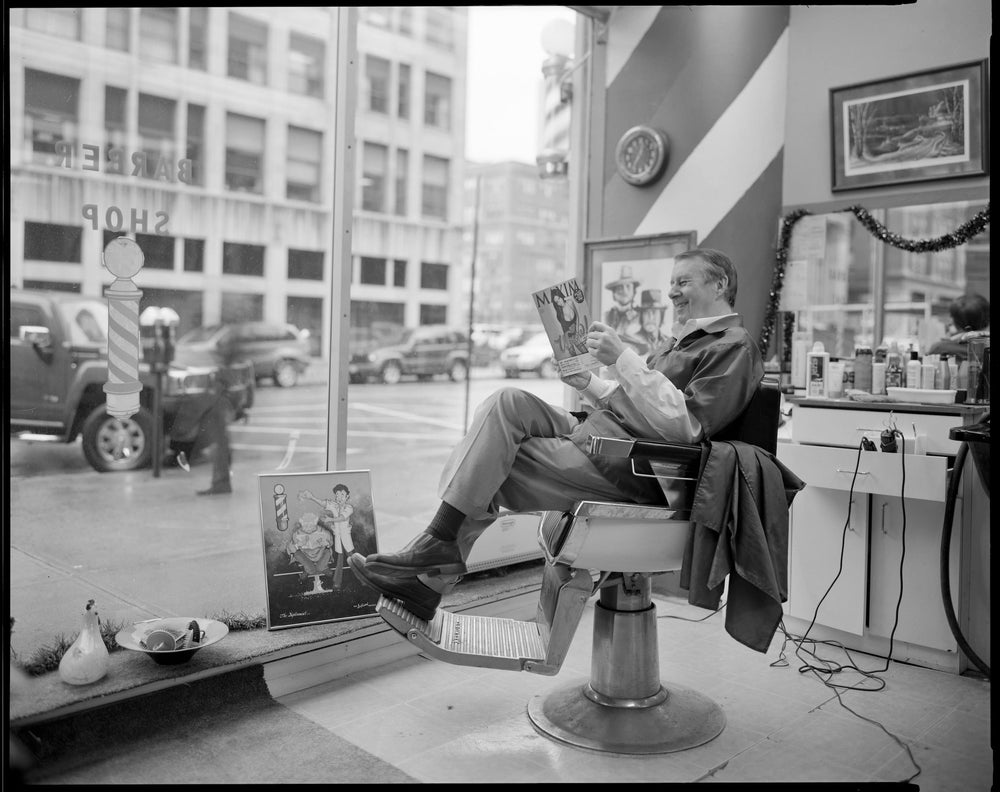

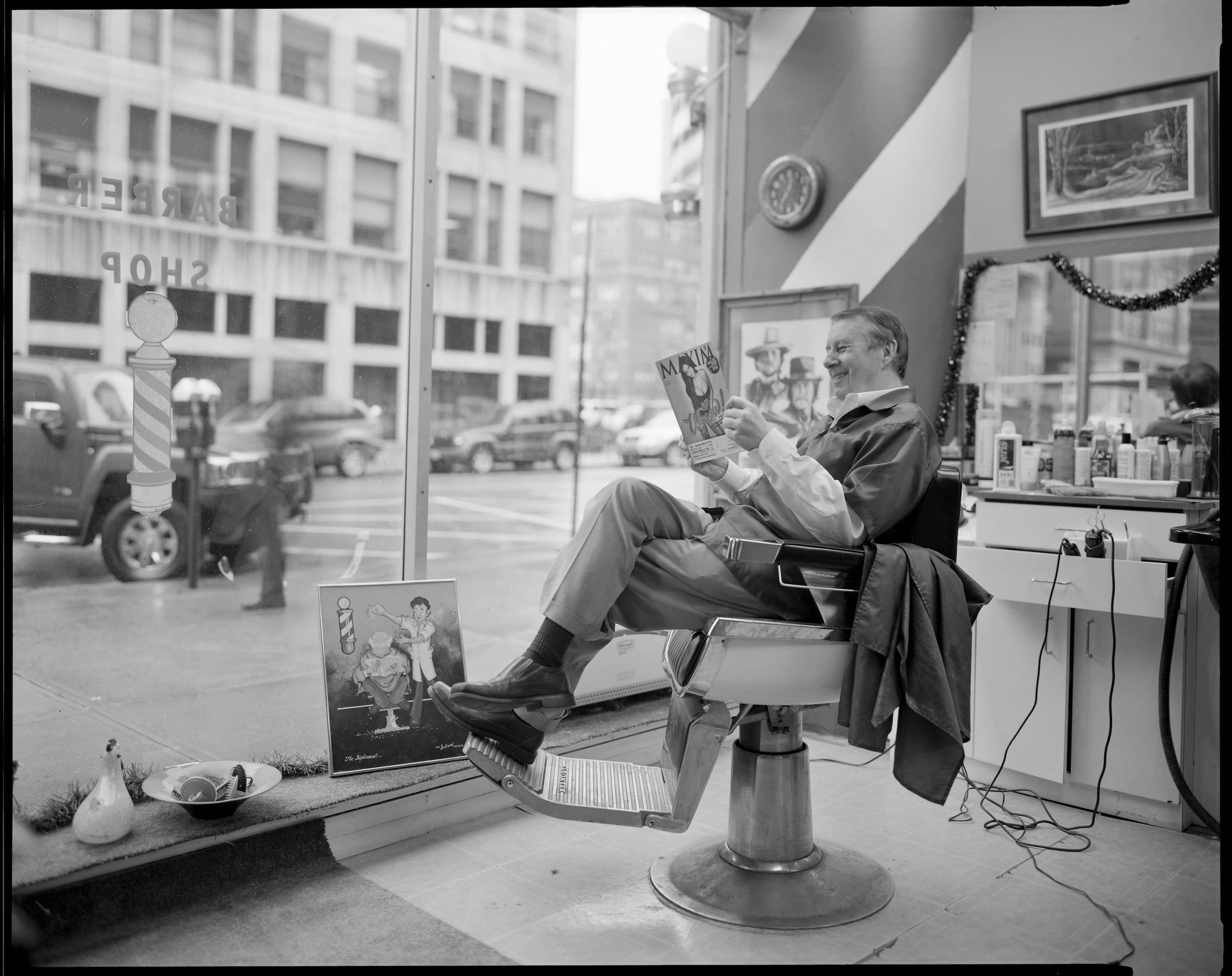

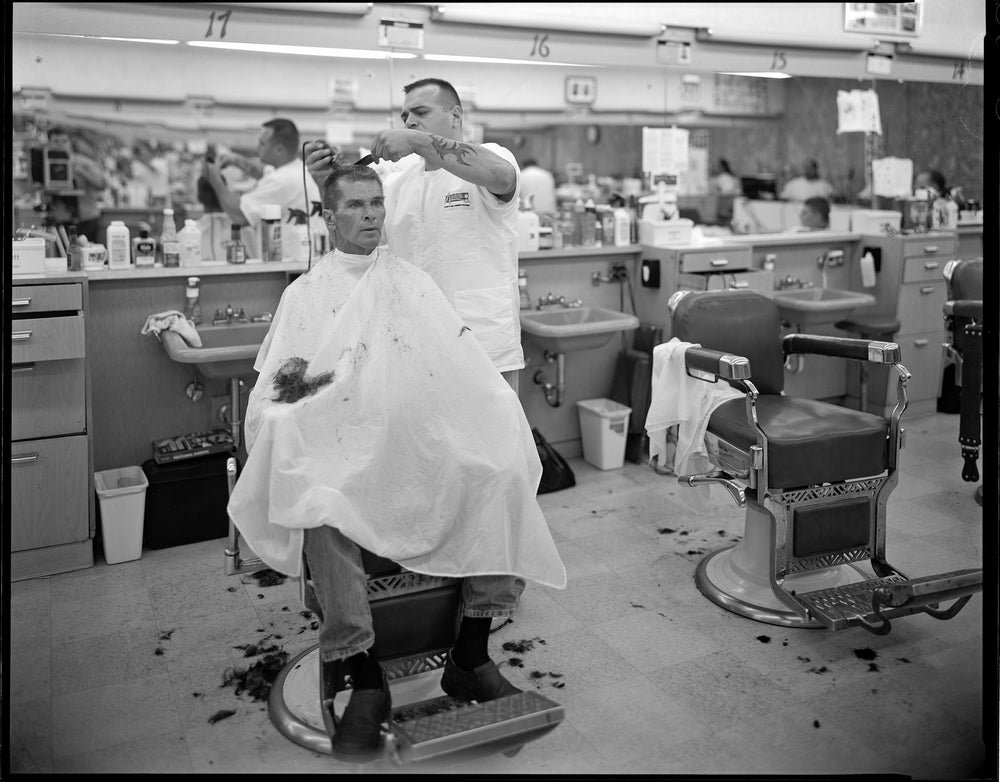

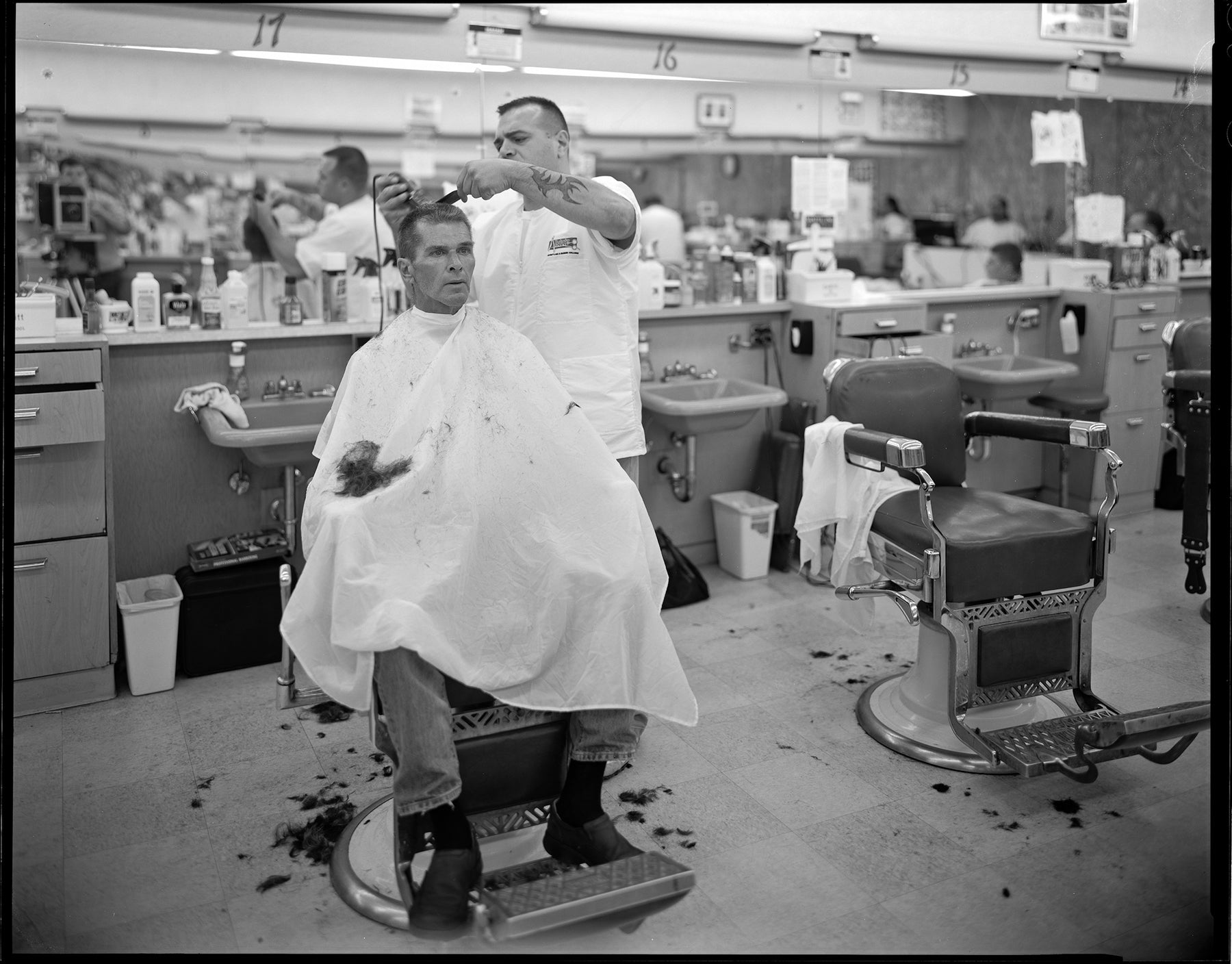

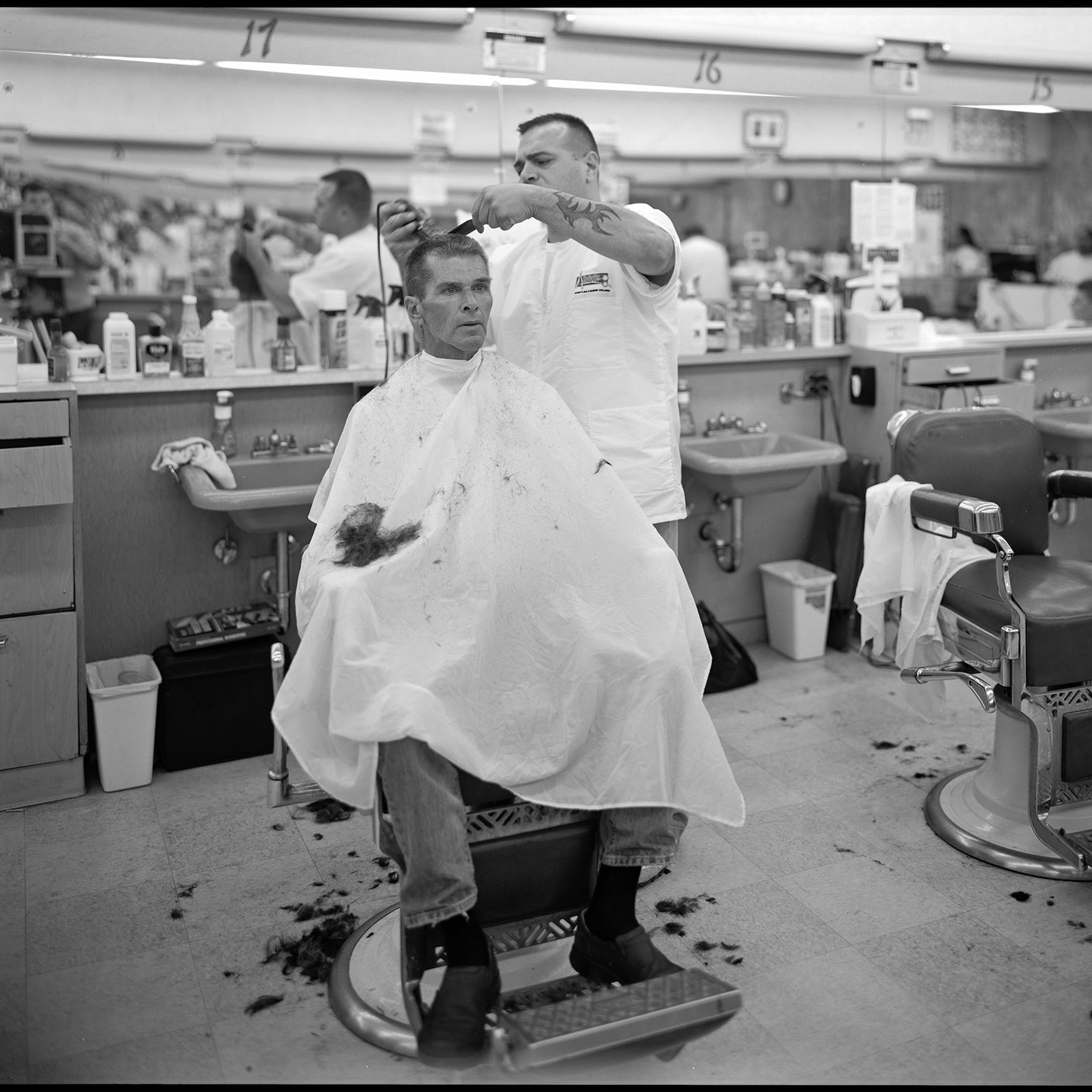

What have you learned pursuing and creating your barbershop photos?

"That was a project that kind of started at the very tail end of that 52 project I did. So that one I was doing on and off from around 2010 through 2012. I still shoot 'em every now and then. But what I learned the most there was how to approach people and ask for a photograph. It was during a time when I was working as a traveling sales rep, so I was going to all of these towns, especially smaller ones, that had quilt shops. I was a fabric rep for a sales company. It was interesting. If you imagine, pharmaceutical reps are usually like, Lakers girls, so they can sell drugs, opioids and such. I was the younger male who would dress up to visit old ladies at quilt shops and sell them fabric. And it was great pay, right out of school. I actually wish I still had that job! But I was young and stupid and wanted to shoot more film. So I went to all these small towns, and they all had taverns, post offices, and barbershops. Of the three, barbershops were the easiest to approach and force myself to shoot. So I would go in, give them the spiel, and not show them the camera, but get them sold on the idea of taking a picture. Most of them were, I learned, really open. They were still the centre of chat in town, even though there's social media and everything. It gave me good practice with people. If I could do it all over again, I'd do the exact same thing but bring strobes, because, god, most of those exposures are like two seconds or half a second, or just something ridiculous. Because people were getting their hair cut it was fine, they could hold still. But I would re-do it with strobes."

When you set up your camera and you're looking for something in nature, what is it that you're looking for?

"Prior to two years ago, I couldn't even answer that question for you. But a photographer whose work I look up to highly— Mr. Alan Ross, Ansel Adams' assistant in the late ‘70s, gave me some really, really good tools to think about what I was looking for in a photograph. I really didn't know until I had him critique my workflow. He was there giving me the feedback I needed. 'Why did you do this step? Why didn't you do this step? What made you look over here instead of over here?' Really valuable questioning and feedback. But the big thing, especially with the newest Ohio pictures that are on the site, a lot of those were going for a feeling, or a sense. The whole uninterrupted part is that everything was very quiet, very calm. There's a lot of growth in the area of Ohio I live right now, in Columbus. It's not quiet, any time of day. So I always looked for a sense of quiet. Sometimes it was unsettling quiet, so a lot of photos have a creepy look. A lot of them were very calm or overall mellow. But the quiet was the prevailing thought throughout those photographs. So whenever I was at a place that had, usually, a good sense of backlight and all the values I want in a photograph—so black to white—if I felt like it had a good sense of that quiet, that space, that welcoming sense of 'you're here,' I'd set up the camera. Go for a feeling, not, 'I saw this on Fstoppers and I think I can do it better.'

What advice would you give people looking to get into large format photography?

"This is where I really do start to sound like a hypocrite. But if I could do it all again—I didn't really choose the camera. I mean, I did, but I just saw it and went with it. If I could do it all again, I think the differences between 4x5 and 8x10 are slight enough that I would strongly recommend that somebody do it all in 4x5. You can work faster, there are more tools, more films, and you can travel a lot lighter. Taking an 8x10 set-up to Africa, and succeeding but still struggling with it was hard. I watched as a buddy of mine had no problem doing all his 4x5 stuff in a carry-on. So I'd do it all again in 4x5, and just force myself to get out and shoot. I really don't believe in the whole inspiration or #blessed kinda stuff. I really just want to get up, force myself to, 'Today I'm gonna go shoot, good or bad, I'm gonna make a picture. I don't have to make a lot. If it's a bad day, I can make one.' But you have to put in that kind of work with it. And when you view other photographers' work, especially on Instagram or anything where you can see the results right away, it's really easy to really unfairly compare all your struggles with everybody else's highlight reel. Just keep your head down and work at it. Work cheaply. If you can't afford the film, don't go broke buying film! Shoot something that works."