Jason Lee's Small Town America

Jason Lee is a true renaissance man. He came up in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s as a skateboarder, cruising around to “The Knife Song” by Milk and alongside other greats like Mark Gonzales and Guy Mariano in the 1991 skate video titled Video Days, partly filmed by Spike Jonze (shortly after, he also founded Stereo Skateboards, which is still kickin’). From there, he went on to act in countless movies, including Mallrats, Vanilla Sky, and Almost Famous, as well as starring in the hit TV show My Name Is Earl as the titular character.

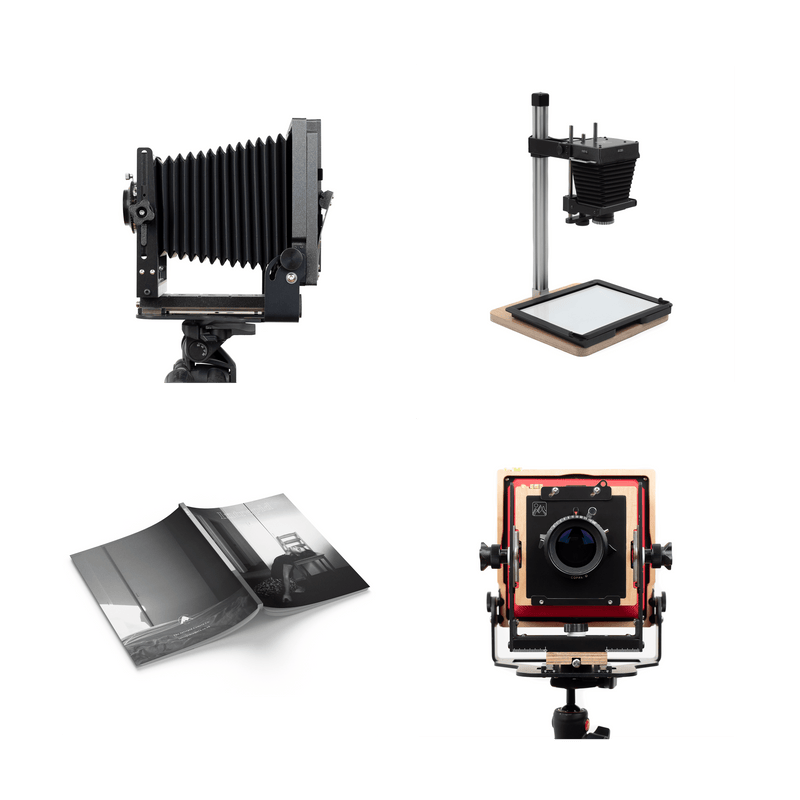

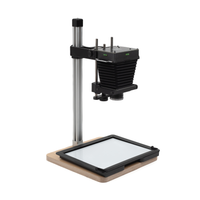

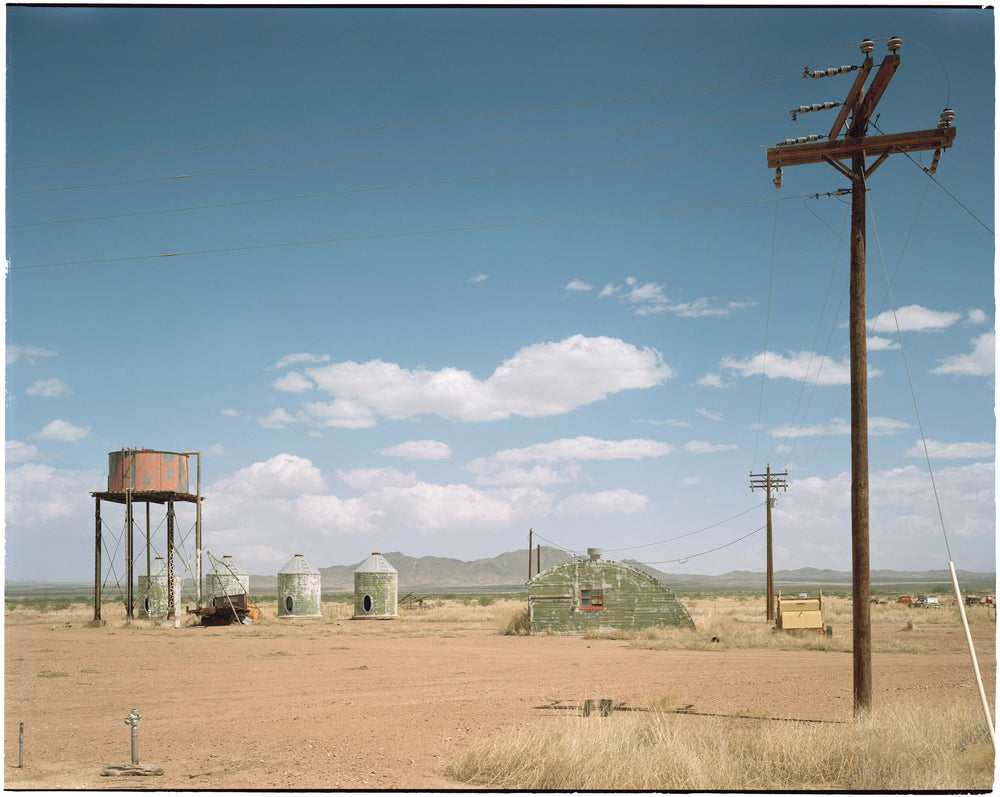

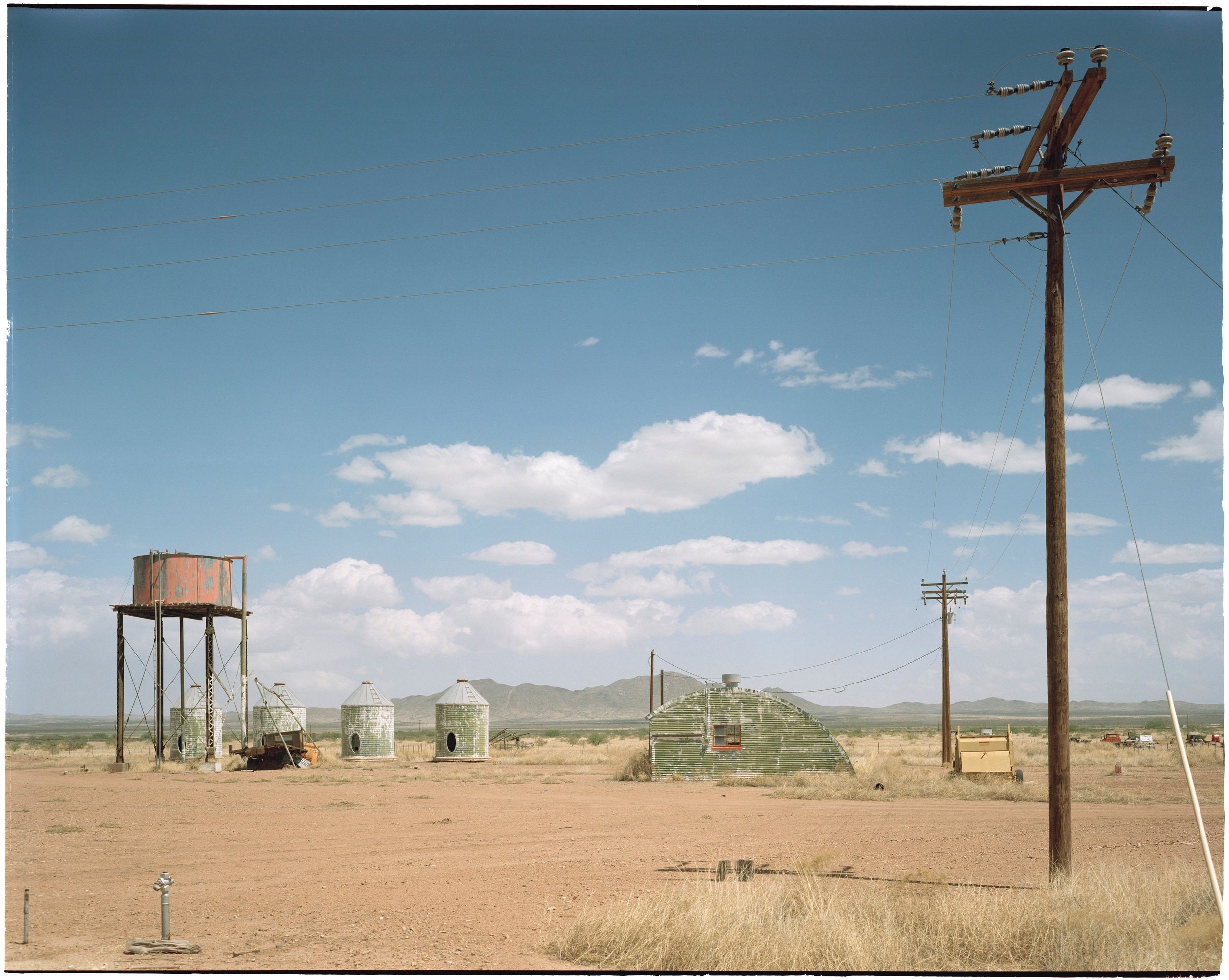

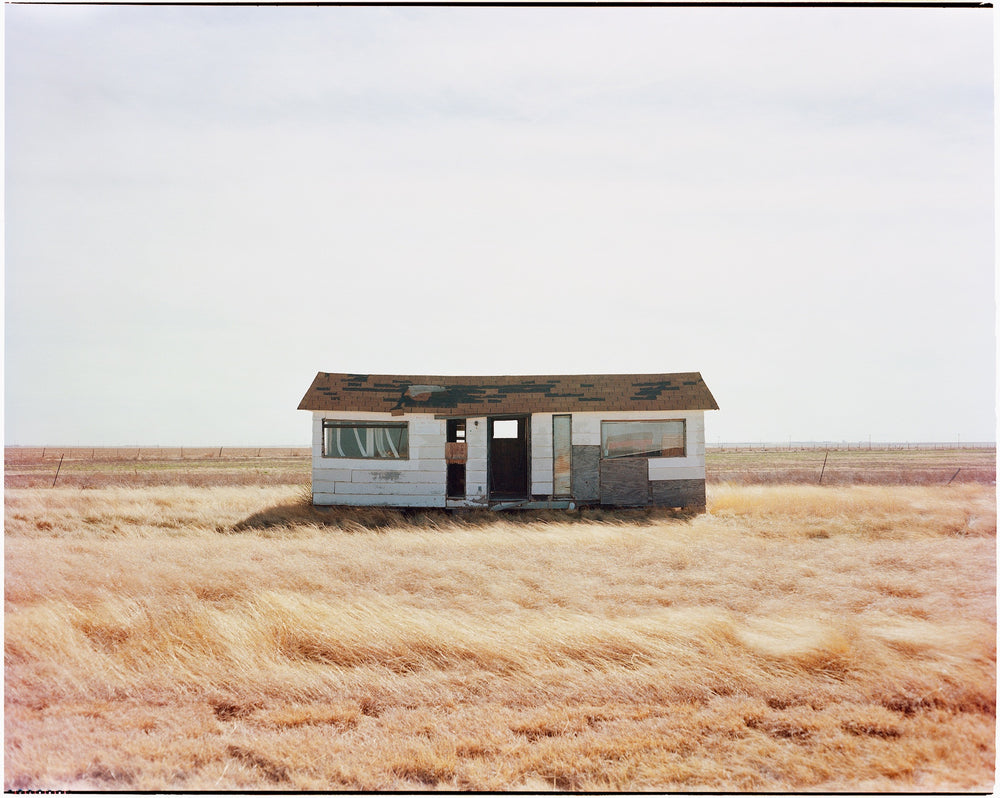

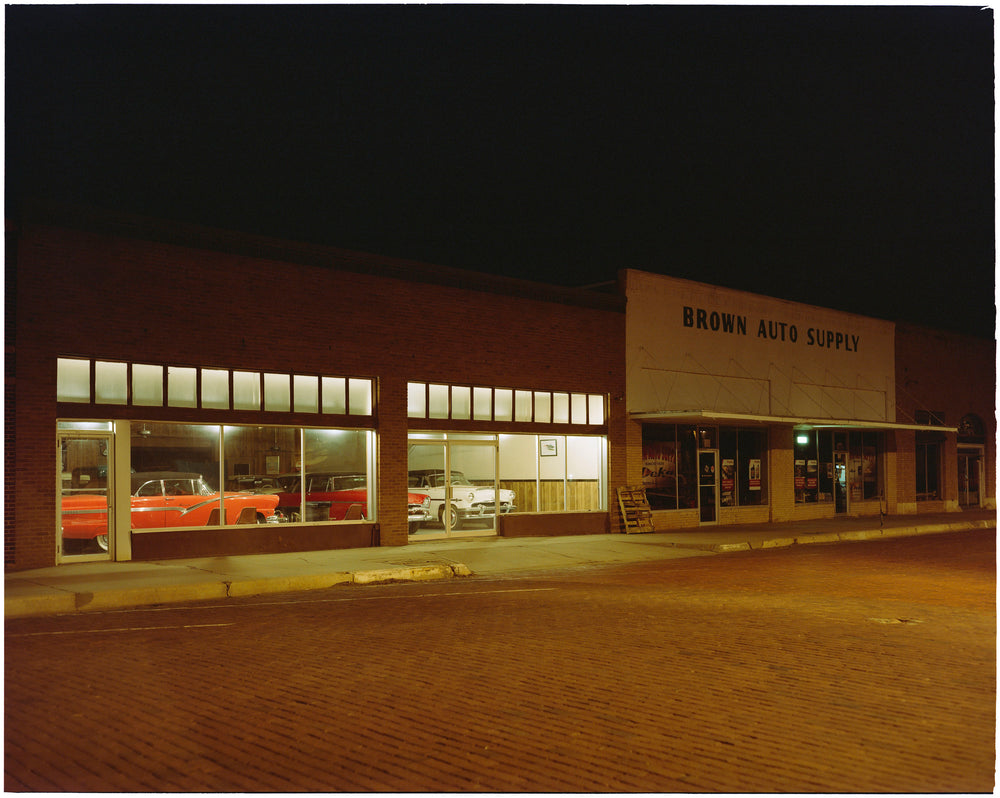

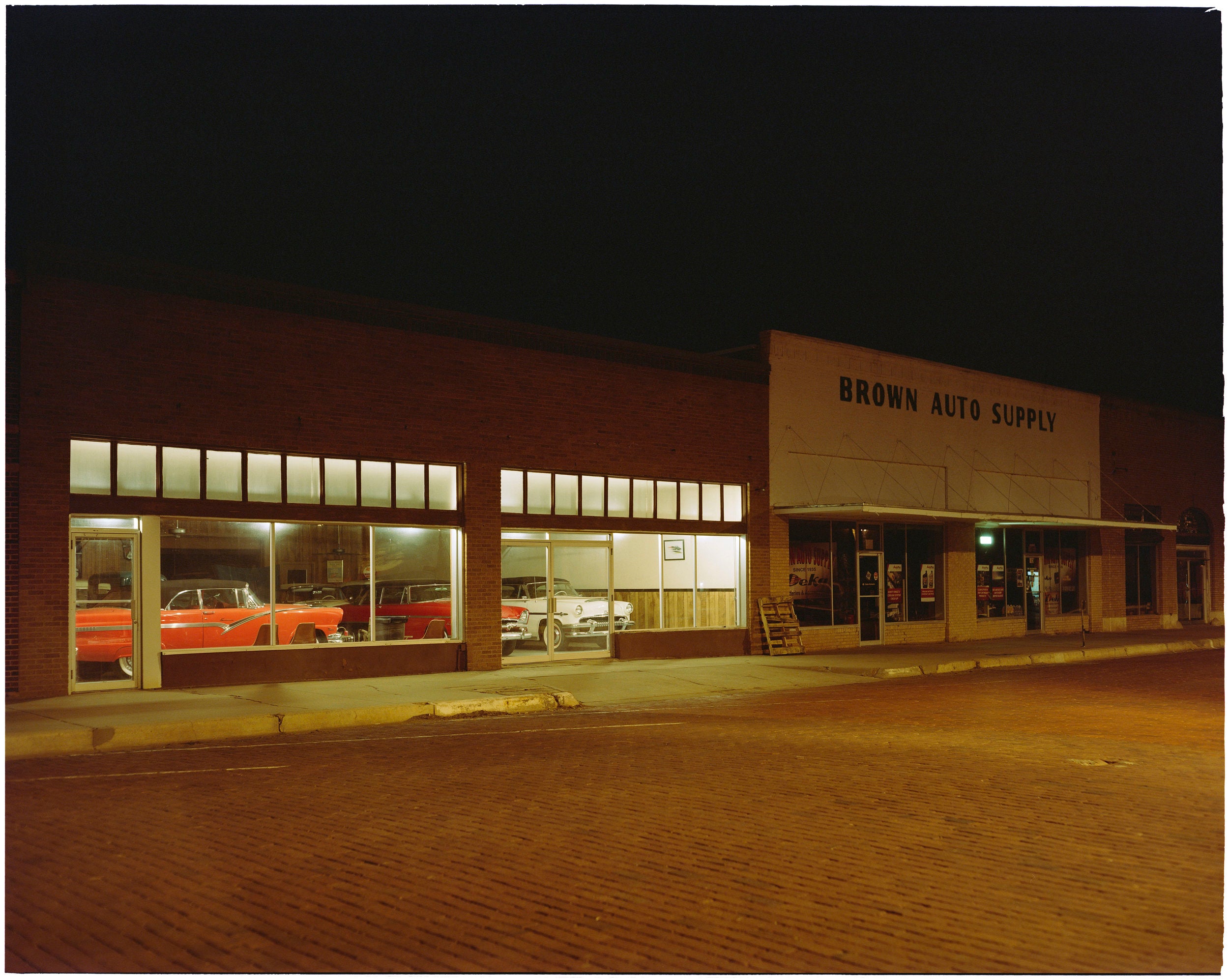

But in the past couple of decades, Lee has also become an avid and prolific film photographer, exploring the American landscapes of his adopted home state of Texas with a Graflex Speed Graphic and expired colour Kodak films for his book A PLAIN VIEW, and more recently putting together a series of photographs shot in Oklahoma for an exhibition at the Philbrook Museum of Art, opening May 31. He’s a founder of Film Photographic, an Instagram account and “co-curated community gallery and resource page by and for film photographers,” and a huge champion of large format photography. Lee’s photos seem to freeze time in a way that’s remarkable even in a medium where it’s par for the course—they often depict small-town scenes, absent of people, imbued with a calmness that’s sometimes eerie, other times deeply comforting.

How did you get started making photos?

"On a movie set back in 2002, I started paying more attention as an actor to the cameras and what goes on with the process of movie-making. In the skateboarding days, about a decade prior, I used little automatic Super-8 film cameras and various Polaroid cameras but hadn’t really made any photographs or known much about the properties and characteristics of film until 2002, when I’d decided to start exploring the medium a lot more seriously."

How did you get started with large format photography, and what drew you to it?

"I was using a lot of Polaroid pack films with my Mamiya RZ67 medium format camera and loved the films so much that I started using them in larger formats—4x5 and 8x10."

How does the way you approach making a photograph change when you’re shooting large format? Does the way you see a shot before you make it change dramatically?

"Nothing changes. For my recent Oklahoma series, for example, I used 35mm, 120 and 4x5 films, bouncing between the three formats, location to location. And it’s never the camera or format that decides what I want to document or not document—I’m drawn to scenes because of the scenes, and I document accordingly. I work really fast, even with the bigger cameras. It’s all very spontaneous, and I think it’s important to maintain a spontaneous energy when photographing, even with larger cameras. I don’t take a lot of time ‘determining the shot,’ but rather I plant my camera where I first saw the scene for the most part."

You live in Texas now and have photographed it extensively—what about the Texas landscape makes you want to capture it?

"Like most of the rural American landscape, it’s full of odd scenes, which always draws my attention. But with Texas, it’s also quite cinematic, in terms of there being those visual references for me, such as Wim Wender’s masterpiece Paris, Texas. For A PLAIN VIEW, I’d also had David Byrne’s film True Stories in mind. I don’t often use colour films, but for A PLAIN VIEW knew I wanted the series to be in colour, as the landscape, those scenes, almost demanded it. But with a particular and fitting palette, hence my use of expired films and an old uncoated lens from 1941."

Your work finds you on the road a lot. How do you find your approach to making photographs changes on the road as opposed to being close to home? Are there specific things you’re searching for? What kind of headspace does that environment put you in?

"It’s always lonely on the road, but I like that feeling. And these rural parts that I’m drawn to lend themselves to that feeling oftentimes. But, when making exposures near home, that sense of being out there and making photographs is unmatched, regardless of where you are. Always music playing in the car, and always on the lookout for the next scene to stop and document."

What are some essential pieces of equipment you take with you on the road for large format photography?

"Dark cloth and light meter, and journal, which is key. Not only for taking notes as to what exposure was made where and with what film, but to make notes at the end of the day—pages for my kids to read later in life about my time on the road."

Can you tell us a bit about your upcoming OK series at the Philbrook Museum of Art? How does it stand apart from your previous work?

"The OK series was one that was commissioned by the museum. They’d seen and enjoyed APV and thought it might be nice if I explored Oklahoma with the same approach. The exhibition is a very involved one, in terms of the number of photographs that will be on display. And unlike APV, I used different formats and both colour and black-and-white films this time around. Oklahoma felt even emptier, lonelier than Texas. And I liked that."

When you look at your body of work so far, do you recognize any themes, moods, or feelings that run through it?

"Yes. It’s always important to me to stand aside, so to speak, and allow the scene to render itself. Distance is key for me. Allowing some space, and for the scene to just be what it is is important. This approach is one that I’ve adhered to since first making photographs from the road back in 2006."

If you had to choose a photograph that defines your last decade making photos, what would it be?

"Hard to pick one, because they all work together in a way. Even if only by distance and palette. It’s the scene itself that I’m most interested in, and sometimes the scenes are interesting, and sometimes they’re just what they are. But it all fits together. And so I don’t think there’s ‘one’ defining one."

As photographers, we’re constantly learning, and I find that there is always something new and consuming to think of in regard to the medium. What about photography is captivating you lately, and why?

"I’m always just impressed by what film is and what it can do. There’s nothing like it. And I’m grateful that it’s still available. I will forever use film, and it’s all I’ve ever known and will ever know. I like experimenting with different types of films and seeing what’s what and what can be done with film—pushing, pulling. There’s always something to learn, as you said. I’m captivated by the whole process of film and photography, always. It’s my greatest inspiration."

Do you have an idea of what project you’d like to embark on next?

"No new photo projects lined up at the moment. I’m swamped making the prints for the Tulsa exhibition, will then move on to laying out the OK book, and then for 2020, publisher Stanley Barker will be releasing a book of selected black-and-white photographs from my archives. And that will be a big undertaking. But I’ll be making more photographs here and there during that time I’m sure."