Jon Paul: The Fine Art of Nature

A little over 20 years ago, Jon Paul—then an Ironman triathlete—moved to South Lake Tahoe, California, with his now wife. Being an avid rock climber and hiker helped him cover huge ground in the area, which he quickly realised contained an astounding amount of natural beauty. “I used to joke around - If I was a photographer, I’d take a picture of that,” Paul says. The joke swiftly turned into a passion that’s been running strong for multiple decades now.

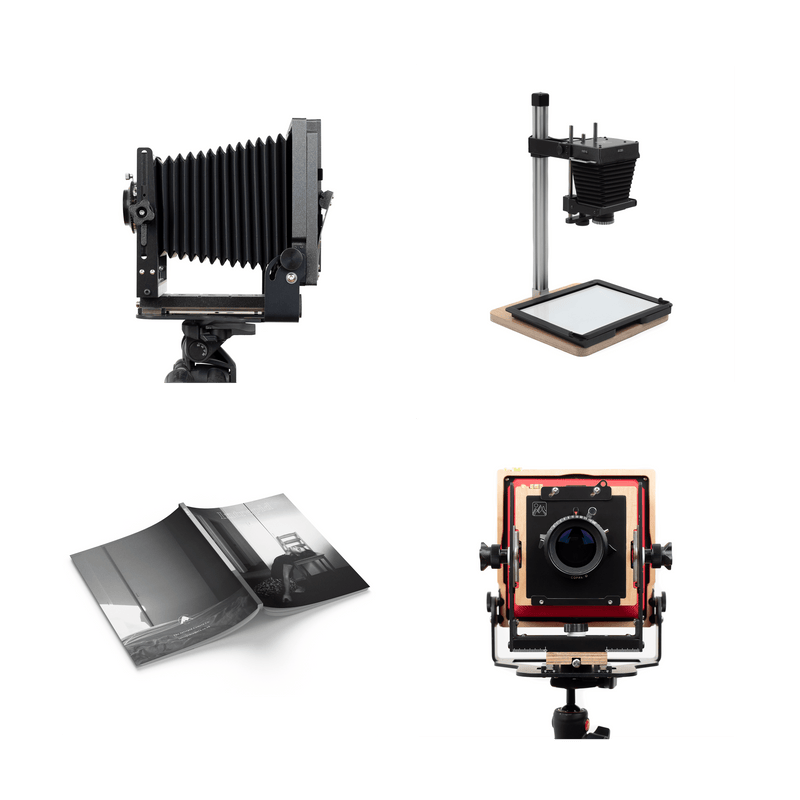

Starting off with a cheap 35mm camera, Paul taught himself how to make decent photographs, and within a matter of months, he was wholesaling them as cards and prints to tourist gift shops in town. Unimpressed with the quality of prints that were available up in the mountains, he bought a 4x5 Super Speed Graphic and a few inexpensive lenses, making his way through the intricacies of large format photography. From day one, he was creating art to make a living, getting the business started, selling landscape photographs on a small scale, shooting portraits and weddings and skiers—anything people would pay him for, pretty much. Now, he sells to collectors in all 50 states and more than 50 countries around the world.

When we speak in late 2018, he’s just finished working on an article for Darkroom Underground and is particularly generous with his time. We cover a lot of ground throughout our conversation, but throughout, Paul stresses one point especially—simplicity is key.

“I'm a firm believer in keeping it extraordinarily simple, and doing the part that got us out there in the first place: going to beautiful places that motivate us and make us happy, and then composing what should be a piece of art as opposed to being mired in a vast amount of technical thought, detail, and process,” Paul says. “Some people enjoy that. I won't knock it. But I take a lot of people out and do workshops, one on one, and there's so much information out there now on the Internet that it's very easy to feel as though we have to learn everything. Sometimes in our effort to learn everything, we don't listen to that little voice inside that's telling us, 'Wow, that's beautiful light, that's a beautiful composition.'"

I think a lot of people, at first, see a large format camera and think it's much more complicated than an electronic machine, and then you start using it and realise it's infinitely more simple.

"That's absolutely it. The downside, I guess, is that it doesn't have a histogram. But I like the fact that, using my spot meter, not only am I very conscious and careful about getting a correct exposure, but I'm also really conscious of why I want to expose a certain way. Do I want to capture everything within the contrast range and latitude of the film, and make my contrast adjustments after the fact? Or do I want to do it with that exposure? But I primarily, on average, only take one exposure. It's a way of forcing myself to really be in charge of what I'm doing, but it also makes me put a lot more responsibility on myself, so I'm not just snapping pictures and hoping one of them comes out. It makes me think, 'Okay, to begin with, I feel like this image is worthy of taking my camera out and producing an image for Jon Paul's Gallery.' But from there, if that's the case, I want to treat it with, I guess you'd say respect and responsibility. It's not just snapping a picture. I'm composing something that moved me enough to go through the trouble of taking the camera out and spending money on film."

What was your early experience like with the Super Speed Graphic?

"The Super Speed Graphic was cool because it has a drop bed, so you can shoot at a wider angle. The thing was built like a tank. You could throw it off a mountain and go down and pick it up and take a picture. But I think it's one of the things that helped me just focus on the basics. There wasn't a vast amount to do. You rotate the back to shoot vertically or horizontally. In essence, it's an empty box, with its own steel case. To this day, for the most part, I still use the same method. The camera I use now has more bellows extension, so if I want to, I can use a longer or a little bit wider lens than I could before, but aside from that I'd say 98% of the movements I use are very simple - front tilt for near/far focus, and on a rare occasion, I'll use back tilt to change perspective, to accentuate foreground subject or a mountain in the distance. But that, honestly, is rare. I think just realising that I was able to use a very simple piece of equipment and a very simple process to capture really fine information on a big sheet of film, that enabled me to do the big prints that I wanted to do from day one."

Can you tell me about The Fine Art of Nature?

"The Fine Art of Nature is kind of what I've just dubbed the work that I do. It relates to my landscape photography overall. So the essence of that is that I really try to push myself to not just go out and take pictures for the sake of taking pictures, and I make the effort, or I choose not to expose a piece of film just because I went to the trouble of getting myself somewhere. What I'm trying to output are images of landscapes that I believe are, and want to represent as, fine art. They're not just volumes of pictures. This fall, most people would say was one of the best fall colour seasons we've had up here in our region in quite a while, but I was just absolutely unmotivated by the compositions I was finding. I literally went out day after day and didn't expose a single sheet of film. There were pretty pictures to be taken, and who knows? Maybe I blew it by not taking some. But they just didn't strike me as special. I could see there were gonna be hundreds of thousands of digital shots captured during the course of that week that were all, 'Oh, look at the bright yellow tree and the blue sky.' Those things aren't bad, by any means, but they also aren't particularly special. I think they're more special as things to go out and experience and take part in, and to use photography as an excuse to be out in a beautiful place, and appreciate what's there. But when it comes to The Fine Art of Nature, as I call it, not everything that I think is beautiful is worthy of a sheet of film."

When you talk about being moved enough to decide to take your camera out, are you familiar enough with what moves you, that you could describe what you're looking for? Or is it more a feeling in that moment?

"I think it starts with the idea that, okay, in this general location, at this time of year, and this time of day or these weather conditions, I roughly have an idea in my head of what I might be hoping for. But basically, I get out, and I'll hike, and most of the successful images I've taken, I feel it. I'm quite literally drawn to a subject and compelled to get the camera out and take a picture. It's a quietly exciting moment where I feel like, 'Oh wow, look at that.' And this is something I'm gonna be moving myself in the direction of more and more, where I'm at a point where I don't want to consider the idea of, 'Am I shooting enough? Am I adding enough volume to my portfolio?' I want to put out images that make me think, 'Wow, that feels great.'"

Would you say it’s dangerous to get into that type of thinking where you're constantly wondering whether you're making enough?

"It's awfully easy. It's the name of the game in today's world. Especially if you dare look at things like the number of followers or likes somebody has, that can be deceptive. I think it's wonderful to share, and you can have a really positive impact on people that way. It's why I have my YouTube channel that I'm intermittently sharing on and hoping it helps or motivates people. And of course it's nice when people call up and say, 'I'd like to learn a little bit more, can I go out on a workshop with you?' But the reality that I'm learning about (that’s worked for me for so many years), is being absolutely genuine with what you share and how you treat people and how you do your art, and I think people really pick up on that—being willing to share information but sharing it for the right reasons. Everyone needs to make a living, so I don't think it's wrong to share information and then let people know that they can also be a customer. But I think people can feel if you're genuine, and if your intentions are honest. It's a really interesting world we live in right now, and I'm trying to learn all about that and how to continue, after a couple of decades, to still make a living doing this, yet at the same time really stay true to what makes me want to create beautiful images and compose the images that really move me. I've been very lucky that the way I see the world, a lot of people happen to appreciate. I don't take that for granted for a minute. It might be to my detriment, but I'd rather walk into an aspen grove that could be anywhere and compose an image that makes someone feel like, 'Wow, right now in the middle of my hectic day in the city, I feel like I'm standing in the middle of this amazing place.'"

Something that feels bigger than the sum of its parts, too—not just an image but a feeling.

"Yeah. And the best way I can share what brought the reality of the impact our work can have on me, is that I've had a surprisingly large number of people share with me that they've set up large images of mine on a wall with dimmers, with a chair that faces the image, and they'll actually use it as a source of meditation for themselves. It's set up in a way that someone would set up a television. A large percentage of those people are people who happen to be battling illness, going through cancer treatments and what have you. I've had several of my collectors, who I tend to get very close to and form friendships with, who have actually used pieces in their own hospice care, as something to bring them peace from the natural world for the end of their lives here.

When I say I'm moved by something, it's not, 'Oh wow, that tree is cool.' Okay sometimes it is, but literally, there are times it's as though I'm physically pulled toward something, and whether I'm in an outright blizzard, or in a rainstorm... I've taken pictures when it was so cold out that I've lost numerous fingernails from frostbite, just because I felt so moved to get the camera out and load a piece of film and expose what I was feeling, so I could share that."

What have been the long-running, consistent challenges throughout your large format practice?

"At times, to be honest, the biggest challenge has very simply been financial. I've got collectors in all 50 states and 50 different countries. I don’t dwell on it but I'm pretty humbled by the thought of that. The reality of it is though that I haven't always been the best marketer, or been focused on the business itself. I haven't been terrible at it, as it's been, really, the sole income of our family for 20 years plus. It's something I'm working on and trying to learn more about now. When it comes to challenges with the equipment itself and being a large format photographer, the only real challenge I've had with it is the simple fact that maybe you're hiking in a beautiful place and you get that fleeting rainbow, over the river that you want to photograph at sunset, and it happens 20 minutes before you planned on actually taking the shot, so you're not there and you can't quite get your camera set up fast enough. That would be the biggest challenge. Aside from that, it can be uncomfortable to have to take so much longer to get set up in really, really bad weather conditions or in awkward locations. But if I walk up to a spot, I can be completely set up in probably less than five minutes. Set up, and hopefully focused and metering the scene, depending on the camera I'm using."

Is it sometimes a bit of a relief to have your enjoyment of a scene like that dictated by your equipment? For example, if you know it's so fleeting that you won't be able to capture it, can you sit back and relax and enjoy it, with the pressure off?

"Nope (laughs). Usually not. I've made a vast effort to be mature enough, I guess you'd say, to make sure that when I'm in a location, doing photography, that I'm also taking the time to step back and look at where I am and what I'm doing and fully, genuinely appreciating it. But I usually relegate that too after I have my film exposed. So when I'm out there, it's not all business. Quite the contrary. I'm out there because I love what I'm seeing and what I'm experiencing, and that's where I'm truly, genuinely happy and feel healthy, which is hugely important. But I find that when I'm actually setting the camera up, and composing my image and preparing to take the picture, I'm really, really happy at that point in time. I'm immersing myself in a process I really love."

It's definitely a way of being present.

"Yeah, absolutely. And back to the beginning of our conversation—not wanting to get overly technical with things—by keeping it really simple and mastering only the basics of composing and focusing and metering, when those start to become almost second nature to you, you can brush those a little bit to the outside of your thought process. Then you're really primarily focusing on what you're moved by, and composing that. After I get my composition set, which is to me the art, then I set the focus. I critically focus it, which usually takes about a minute, and then I can relax, and I put a piece of film in the camera and meter my scene. Which again, takes 30 seconds. So those three little things, I'm comfortable with them, they don't take long to learn, and that enables me even more so to just revel in where I am and the fact that my whole objective is to go to a beautiful place and compose an image of one little spectacular piece of it. That is not terrible."

How has photographing these places helped shape your relationship with them?

"It's made me amazingly sensitive to the fact that a majority of places are now overcrowded and overrun with people who want to go out and take pictures of them, primarily digital. And it's not digital photography's fault, but I am one of the growing number of photographers now that is feeling pretty strongly that when we do social media posts and what have you, we don't necessarily divulge exact locations. I've got some places I've gone every year—national parks, for example—and as photographers, we've always been able to go to these places in the offseason and in the fall, for example, and it's cold and wet and beautiful. But for forever, the only people we would see there would be a handful of professional photographers. It was quiet, and you could have your own space and it felt like wilderness. Now, these places are to a point where in the offseason, not only are you standing next to 300 people taking a picture, but you can't find a place to camp, let alone a hotel room. Slowly, I'm backing myself away from some places I really love. Fortunately for me, it fits into the style of photography I'm a little more known for, which is the intimate landscape. So I can run away into the forest or go hide in an ice cave or something. The thing is, I don't think people are wrong for wanting to be out there. But as you get a larger group of people, not only does it take away from the serenity and the natural qualities of the place, but the larger the group, the more likely that there are going to be one or two or more people who find that them getting a picture is more important than ethics and environmental practice and respect for others or respect for the wildlife. Those one or two people, as we've always said, ruin it for everyone else. It's not always the case, but more and more I'm choosing to eliminate myself from those situations. A) I don't enjoy it, and B) I don't wanna become part of the problem, because I also feel the ice hockey player in my wanting to come out. A whole aspect of outdoor photography, for me and for many people I know, is that we're there because we respect the solitude of the outdoors and its health. Crowds minimise both of those things."

It reminds me of how I felt when I realised I could make decent photographs—all of a sudden taking a photo of something just to document it wasn’t appealing anymore. A million people had likely done it and a million more will do it in the future. At the same time, it's an impulse I obviously understand, because that's the way a lot of people get started with photography and I'm not sure if there are any photographers who are above, every once in a while, just wanting to grab a shot of something.

"There's a reality to it, also, right? There are certain shots that, if I take this shot, I'm gonna make money. I'll share an example. Because I teach workshops and do wildlife photography, I own digital equipment. On a side-note, when I closed my physical gallery after whatever it was, 12 or 14 years—now I have other people sell my work—I took a year where I had a lot of time all of a sudden, and I wanted to make sure I was not being arrogant or closed-minded, and I only shot with a professional digital camera for an entire year. I didn't print a single image from that year. That said, a lot of people are in love with things you can only do with a digital camera, like photographing the Milky Way. I will tell you, it's a whole lot of fun to go out late at night and be out in a quiet, beautiful place. It's a wonderful feeling. It's a blast to take neat Milky Way pictures at night. I'm not extraordinarily impressed with it because all you need is a wide-angle lens that's fast, an expensive full-frame camera, and very specifically, a recipe that will allow you to get a good exposure with a short enough exposure time to get the Milky Way to show up. Then you work on it in Lightroom and Photoshop to make it look the way we envision. It's absolutely easy. I occasionally take those because someone pays me to go out and do it with them and teach them how. Also, because it is fun and enjoyable, and finally, because people will buy them from me. I'm not emotionally invested, I'm not extraordinarily proud of the images the same way I am with a shot I take with an 8x10, but what's right or wrong?"

I guess then it allows you to keep doing the large format stuff?

"Yeah. If I sell a 40x60 inch Milky Way photo, that pays for a lot of 8x10 film. The other thing is, I'm not duping anyone. I'm not doing anything dishonest, I just find that going out and taking a digital picture like that, that can be pre-planned and pre-visualized down to the exact settings of the camera in the exact spot where you're gonna stand, from an artistic standpoint, I find it to be, 'So what?' It's fun, there's nothing wrong with it, I like being out there, but that's something that in general I do as a business person as opposed to what I see myself as, which is a large format film photographer that shares beautiful, clear, large-scale prints with collectors."

What would you say keeps you coming back to large format? Why does it continue to be your preference?

"There are two things. One, the qualities of the very large prints, because—I almost want to say on a subconscious level—I believe they look strongly different than a digital print. You can stitch a whole bunch of images together, get a high resolution, and get a really big, digital print, or print from digital capture, I should say, and it'll be sharp. But a large print from a big piece of film, as opposed to being sharp, is clear. The details are simply larger. There's a clarity to it, as opposed to a sharpness, which I think is much more pleasing to look at. And the other aspect of it, which I found that year where I shot only professional digital gear, is that when there is not a cost—meaning, having to buy film and pay to process it and what have you—and there's not an extreme consequence—I can look at my histogram and know I have the shot, whereas with film if I did not do it right, it's gone forever, because I won't know until I develop that film—I am a very different photographer. That may not hold true for others. I wouldn't impose that upon anyone else, because people tell me all the time, 'Just shoot your digital the way you shoot your film camera,' and for whatever reason, my brain doesn't work that way. When I go out with my film camera, the fact that there are consequences and costs and there's the effort to take the huge pack off my back and set everything up, I find that I only take the camera out if I really feel there's something meaningful to translate and compose and share. So it's very, very different. My mindset is different and my emotion is different."

Putting that level of thinking into it, too, makes it so much more valuable.

"To phrase it differently, it removes the simple thoughts of, 'I've gotta capture this,' and it moves you more toward, 'Oh, I'm compelled, I feel something here, and I'm moved to do it.' I don't know if that verbalizes it well, but there's such a vast difference for me between, 'I'm out on a commercial shoot and this looks really good so I've gotta shoot this,' as opposed to when I'm off in the forest with my 4x5 or 8x10 and I may think, 'That's nice,' but unless something inside of me, emotionally, is moved... Being emotionally compelled to take the picture instead of thinking, superficially, 'This is nice, I'm gonna snap it.'"

Essentially the difference between a reaction and a decision.

"Yeah, I think so."

What advice would you give people looking to get into large format photography?

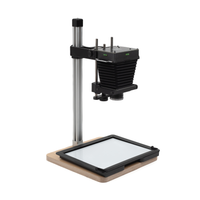

The advice I always give is ‘do it’—especially now, with things like the Intrepid Camera. It doesn't have to be an expensive venture. You can get lenses used, film holders, because people are moving to digital. But I think the biggest thing is just don't be intimidated. Go and learn only the basics, and it's actually a pretty simple process to get into. I think people need to just do it. It no longer needs to be a major financial investment, but don't get overwhelmed with all of the things you may be able to do. I'm gonna be doing some e-books and instructional videos that are focused on simplicity of process, to help people get past that intimidation factor. But quite literally, keep it simple. Don't be afraid of it. And depending on the film you're using, a lot of film is very forgiving. Black and white you can develop on your own if you care to start that way. I use a cross-platform, where I shoot film, develop film, then scan it and use my digital darkroom, which most people already have and are familiar with. So that also incorporates the best of both worlds, and a lot of equipment most people already own. Most people who are gonna try using a 4x5 field camera need the camera, a lens, you can fake a dark cloth, you need a film holder and film. Everything else—you've got a computer, a lot of people already have a scanner. It doesn't have to be a huge investment, just keep it simple, and don't be intimidated by it. Get involved, there are a lot of great resources out there.