Exploring the Instant Photography of Kevin Mason

"I think the key element always is that I like to make a real tangible thing, something that can be held, or if you are looking online, something that you know also exists as an object in the present."

"Currently based in Berlin, Kevin Mason made a name for himself running commercial studios, before breaking off to work predominantly on his own ideas.

His personal work shows a fascination with both realness and experimental styles, and through rejecting the norms of fashion photography he inadvertently challenges them. His latest work is all shot on instant film, while there’s a physicality to the format, “a dud polaroid isn’t crushing, it's so temporary, you just take another one, but unlike digital, there is no expectation to take another.”

Could you tell us a little about yourself and your photography background?

Currently, right now, I am sitting at my Mac watching snow whirl around outside my window in Berlin, trying to figure out what are the most relevant elements of the story that I tell myself, and which of those parts to write to contribute to this article. I guess a little about myself, is that I am a photographer, who recently moved back to Berlin to focus on doing something really personal, whether that's making work, writing, or just existing and riding to parks. My photography background is varied, I studied Architecture at Uni, but ended up making loads of skate videos, rejecting drawing and focusing on photography, cut and paste, and photocopies. I was interested in the presence of the person in space, and with photocopies, I was really into repetition and the over-scaling of images until they fell apart.

Skip a bunch of wasted years and I opened a photo studio in Brighton, UK, with a friend using money I’d saved teaching basic studio lighting at weekends. The studio was a real success creatively, it became a bit of a hub for people to hang out, make work, put on DIY expos and become interns. The studio side of things kept growing until after a few years, and an expansion into a 4 studio complex and gallery, I then found myself moving from a studio owner to taking the role of photography manager of Amazon Fashion EU, overseeing the model photography of one of Europe’s biggest studios. I jumped ship after 2 years, moved to Lisbon, and then Berlin, and started to make personal work again until after 6 months Topshop asked me to come and manage their studio in North London. It was pretty much my dream job, so I went back to London, trying to apply the values I hold to a commercial fashion retail business, things such as authentic imagery, minimal retouch, minimal make-up, and creating a studio that was a fun, inclusive, and welcoming space and didn’t feel corporate.

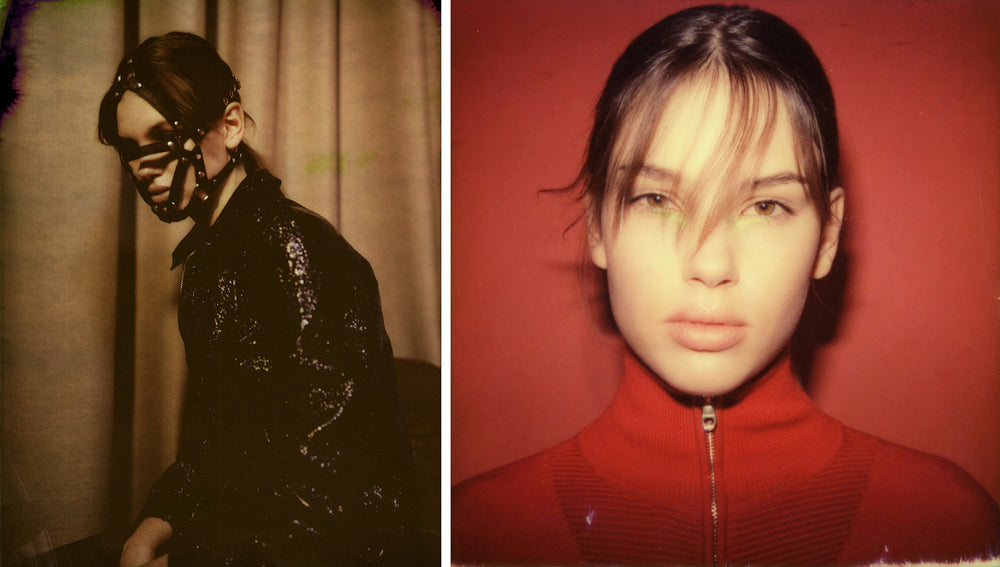

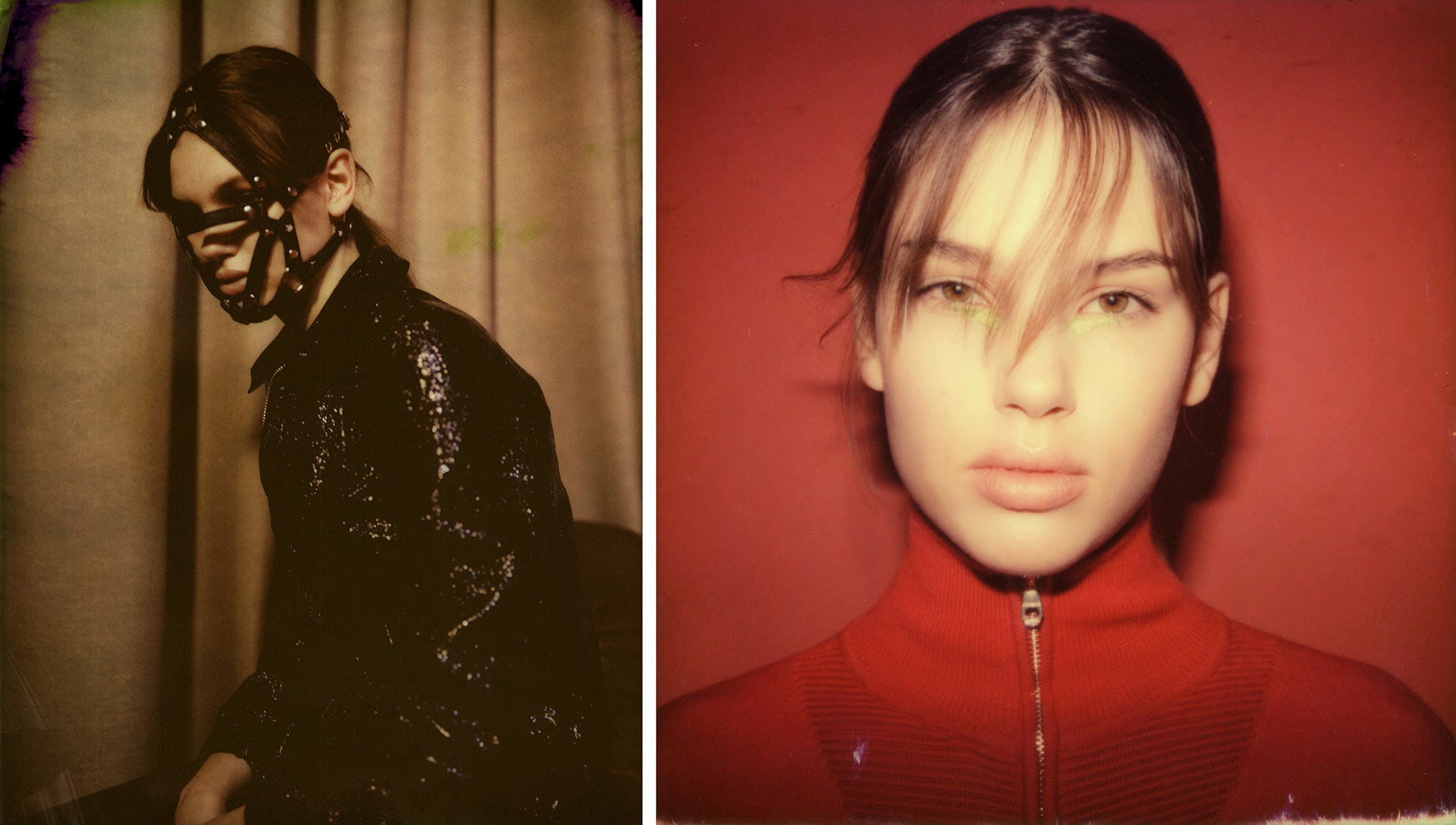

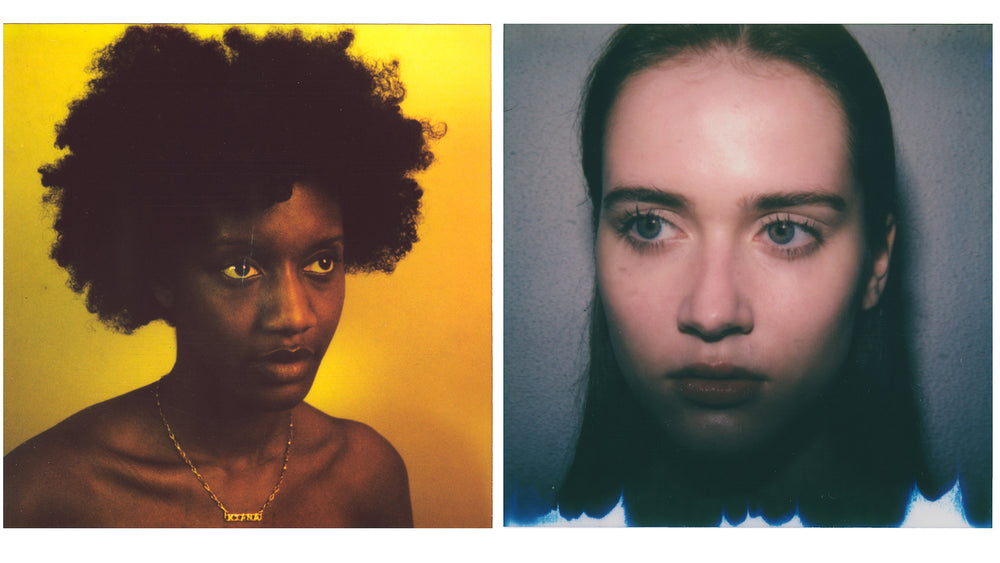

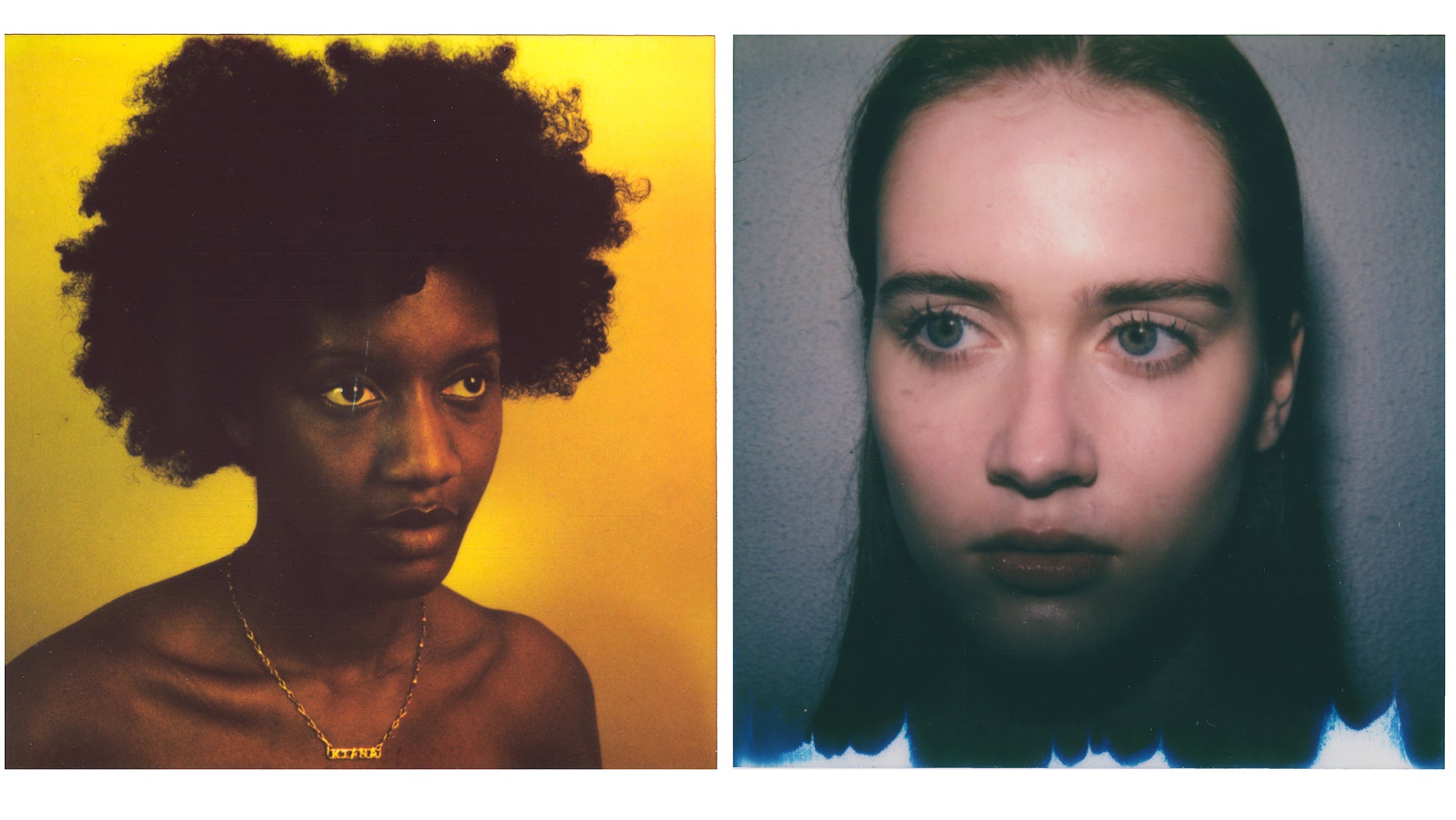

In mid-June of 2018, I moved back to Berlin to concentrate on my own work, get back to scanning my archive and provide studio consultancy to brands working in fashion e-commerce. I also provide lighting direction to photographers on editorial and commercial shoots. Berlin so far has been good to me, I have a shared studio space that costs per month what a half-day hire in a small London studio would cost. I have two main projects on the go, one around make-up masks, inspired by latex/fetish, Leigh Bowery and painting, and the second is focused on millennials, anxiety and the stories we tell ourselves. Over the years my photography has moved from big set builds, and large teams creating covers for magazines to a much more simplified and direct approach, I’ve deliberately tried to strip everything back, so I am really only left with a face and a background.

What draws you to analogue photography, and in particular large format?

"Right now my work is focused on Polaroid (which has been a 10-12 year love affair), and other instant film formats, a year ago I was really into albumen prints, a process using paper soaked in albumen (egg white), and silver nitrate which is placed in a glass negative. I think the key element always is that I like to make a real tangible thing, something that can be held, or if you are looking online, something that you know also exists as an object in the present. Through an inability to fund a legal battle I lost the rights to about 6 years of work some time back and although I always loved Polaroid I think it was the added push to make something that wasn’t just a digital asset. Analog for me, and I know it's very much back on trend (which is only a good thing), is about real joy, it sounds so cliched but I don’t get the same feeling after a digital shoot. I can’t gaze longingly at an orange LaCie drive on a desk, but a stack of polaroids gives me a real kick. The biggest incentive for Polaroid comes down to two key elements for me, 1- the actual final object was in the room with the person, and 2- Polaroid (and for this, I mean all instant film) is a great leveller of people. No one gets worried in front of a polaroid camera, it's throwaway, it's forgivable for its flaws, people forget to pose, they don’t consciously try and push their best side to the camera. A dud polaroid isn’t crushing, it's so temporary, you just take another one, but unlike digital, there is no expectation to take another.

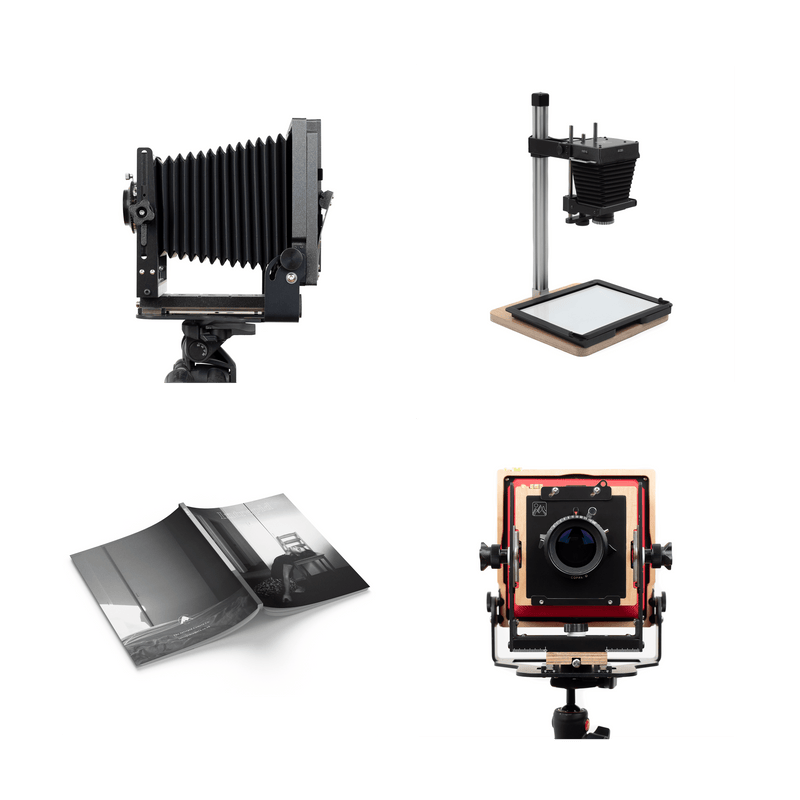

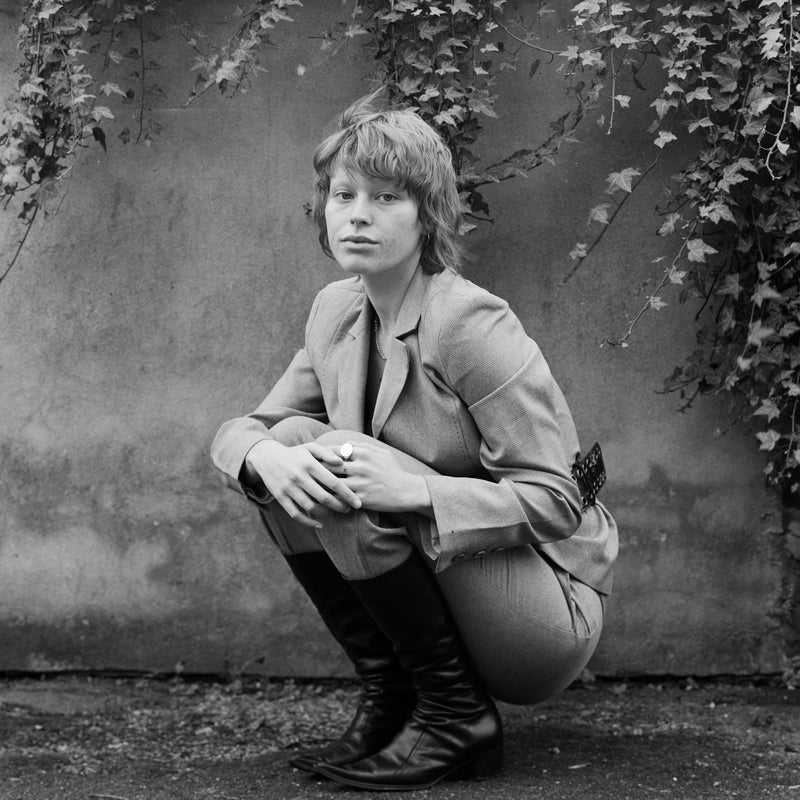

Digital images are likes viruses, they just spawn more and more versions of themselves, tiffs/raws/jpegs/PSDs, variants in Capture1, versions in PS, it's endless, each file getting further away from the original. With instant film, no matter what you do with it, somehow it always references this original object, this item that was with you, it has a reason for being, something that I just don’t see in a digital file. I got into Large format because I was looking for a way to get closer, get more detail, take fewer pictures and slow down. My first full project on large format was the Raw Faces on 10x8 which I shot at the Polaroid studio in Berlin when they were still Impossible Project and huge thanks to that team for being so supportive! They loaned me their camera, their studio and expertise, it was a great experience.

What I like about large format now, is it's very deliberate, it's a lot of staring, and not pushing models to ‘pose’ but creating a small framed space in which a tiny event occurs. Then there of course is the waiting around whilst the picture develops, it teaches the act of being present, which is mostly absent in digital workflows as the file passes from the camera to a cable, to a Mac, to a Digitech, gets converted, and interpolated by an algorithm etc etc. How I work now, you shoot one picture, then you all wait, either relaxed or nervously, until you get to peel it apart or it develops. In that time I could have shot 200 digital frames, it's about minimalism I guess, paring something down to whatever is absolutely vital. I ended up buying an Intrepid because I didn’t think I had the rail racking on my Speed Graphic that I need for my headshots if I'm honest I just thought it was cheap enough that if it didn’t work then I hadn’t lost anything. It turned out to be an awesome camera, I like how DIY it looks, how basic. It kinda looks like the pictures would be basic too. I'm drawn to that."

It could be said much of your work challenges conventional approaches to fashion photography, is this something you actively try and do?

"Right now I’m concentrating on shooting faces and leaning towards beauty but my work is a rejection of established conventions of artifice and retouching. It's not to say it's free from staged elements, but hopefully, it's apparent in the picture what’s real and what is added. Conventional beauty, or at least on platforms such as Instagram is quite niche now and there is an expectation that all these specific steps will be taken and I don’t want to work like that. All those faces that look the same, flawless, perfect, and I just don’t know what it's saying. I like a certain rawness and sincerity. I like Bruce Gilden, I was immediately hooked on Maxine Leonards's Beauty Papers, that's the way Beauty is moving to me. Almost everyone I shoot is from an agency, if a model who has been selected, guided, curated and presented to the world is still not flawless enough to be shown as they really are then I don’t know what we are all doing. What makes this difficult is that I am shooting for myself and I think it’s fair to say not many model bookers love my work, or get excited by it, it’s not classic beauty, it is sometimes flawed and so it’s hard to find the right girls. My aim also is really to embrace diversity which is easier in London than in Berlin at this point. The recent make-up series I’ve started with Victoria Reuter is a good example, we both love it and have fun experimenting but convincing agencies to send me girls is tricky.

My frame of reference isn’t changing, about 3 years ago I realised what I wanted to do and I’m not going to suddenly start lighting really sympathetically and handing files out to beauty retouchers, if anything I think I’m just trying to get more honest with my work. I know I do want to work with really confident agency models and I don’t want to waste a model's time, because that's their livelihood and I have to be respectful of that too.

I think there are really important discussions being had online around what a model really looks like, our perceptions, what’s being done to our psyche by Instagram and Beauty campaigns created from composite shots, and eyebrows that are entirely reconstructed by a retoucher, where skin is created by adobe textures and nothing is representative of what’s real. It is a mental health issue, it's not like mixing an album track, where the listener knows that the process happened, it's a human face, and it's mostly fake yet presented back to us as honest and it's being used to sell us all self-doubt and anxiety. Fortunately, it's changing though and more work is being made all over that plays with these notions. I think that by using Polaroid and prints, it's more obvious that this is a representation of an object, of a face, everyone looking at a Polaroid on an iPhone knows they aren’t looking at the real thing itself."

You’ve shot lots of FP100c, are you mourning the loss like many others?

"Yes, its a real loss, and I say that not just because it's my favourite medium, but because, like others, I have invested time and money into systems that work with it, and now it's becoming so scarce and so expensive that it's taking the fun and experimentation away from work being made. 60 Euros for a box is ridiculous. I am not sure what to move to next, I will look at 4x5 film, but I am also considering paper negatives and other techniques. A loss of materials can be good, it can force you to adapt and respond I guess. If anything right now I'm mourning the fact that I have found a way of working that I love, after years of experimenting and soon it's going to end. But ultimately the sad part of the demise of Fp100 is that they had this beautiful ‘thing’, something really crafted and I wonder what will take its place."

Much of your work has a sense of experimentation, do you have an idea in your head of the end goal then try and recreate it or is more of a process that develops along the way and ends with something you are happy with?

"In the set build days it used to be that I sketched every element of my pictures, nothing was left to chance, I’d spot-sample paint and get it mixed specifically just for a door frame etc. I’d get pretty stressed if a room that six people helped build didn’t look like the sketch. Then I started the Vanity Project with Georgie Hobday and learned to let go and to be led by simplicity. I also did 2 years of therapy to deal with personal issues and during that, I began to learn how to apply failure as part of practice. I used to be terrified of looking stupid in front of people and the fear made me seem super arrogant and fear led me to control every element. So now when I work I don’t really need to direct, I just keep things slow and point my camera and create a small space for an event and take the picture in front of me. I can still stage something but I don’t want my photo to be a lie. Fundamentally right now I want it to be the same thing you’d see if you stood behind me when I took it. I think I’ve been on this really determined path to simplicity that had lasted about a fair few years until I can strip everything away. I get that to some people it’s boring but personally, I find it beautiful. I have a brain that really thrives on routine and repetition. So it makes sense to me that I follow a similar approach to my work, ‘if I could just take a straight headshot’ is what I think when I’m standing opposite a model. It’s closer to just documenting people than making images, but I do get really into a new process, Albumen prints for example. I think if you really focus in on cutting out the extra stuff you don’t need, that you begin to experiment but under narrow parameters and I like that.

A few years back, I had a bit of an internet following, and I started to make work I thought others would want to see, and it was really dangerous for me. I think the concept of the internet can make the mind disassociate fairly easily and having an online brain and a physical brain was pretty impactful for my thought process so I had to learn to make photos that I only I wanted to make and to not consider my audience again. I deleted and destroyed most of the work, and started again. So, yes I have an idea in my head, in as much as I want it to be simple and direct, but the process in which the image comes out does remain fairly open. The two current makeup series included here, are me really ceding control to the MUA and not jumping in with ideas, just giving a little nudge and an open brief and then having fun with it. It’s really loose and freeing, I don’t have this fear of it all falling apart."

How do you edit and scan your photos?

"I just use a basic Epson scanner and Vuescan. I made some film holders to avoid Newtonian rings. I do make colour adjustments to the scans and I clean them in terms of dust etc. I don’t hold the view that a Polaroid is untouchable, I’ll tweak it for curves, colour balance etc, and I’ll remove dust spots if they are really distracting but that’s about it. I scan them at a resolution that allows me to make large prints (around 80cm) as I’m slowly aiming towards a Polaroid expo in the future. For Fp100 I just bleach the negatives and scan those, the print is just a reference point. If I am making Albumen prints, then that’s always from a scan originally not from a contact print approach."

What would you say are the biggest challenges to shooting film for this sort of work?

"The biggest challenges are the raw material costs - it’s really a huge consideration, but to be honest I’d feel that even if I was a painter, that somehow I’d feel I was using too much paint, or being wasteful. I struggle with the concept of playing with materials, as much as I try and deal with that. The time involved, if I shoot a full beauty story on Polaroid and Fp100c, then the scanning and file prep, bleaching the negs, drying and scanning them, all those things take a real amount of time- longer than shooting digital and doing a full retouch. Also for the HMUA, it can be a challenge not being able to see how an eye looks at 100% on a monitor screen on-set, it's why I really love working with a small team who know how I shoot. Everyone isn’t crowded around a monitor observing, instead, they are all looking at the real live model who is stood on set. Also the whole archiving process, and storage of negs, boxes of fresh film and so on, means you need more space. And as I have mentioned before, with the model agencies, if you’ve only shot say 4-6 pictures and they don’t like them you don’t have a fallback of digital simple shots to send them, all of those things make it harder, but not so much that it turns me away from working like this. The idea that you have actual things, objects, proof that you were there, that is worth more than all the hassle and costs."