Exploring California’s Eastern Sierra

Justin Lowery explores California's Eastern Sierra, Nevada Mountains and begins his large format journey.

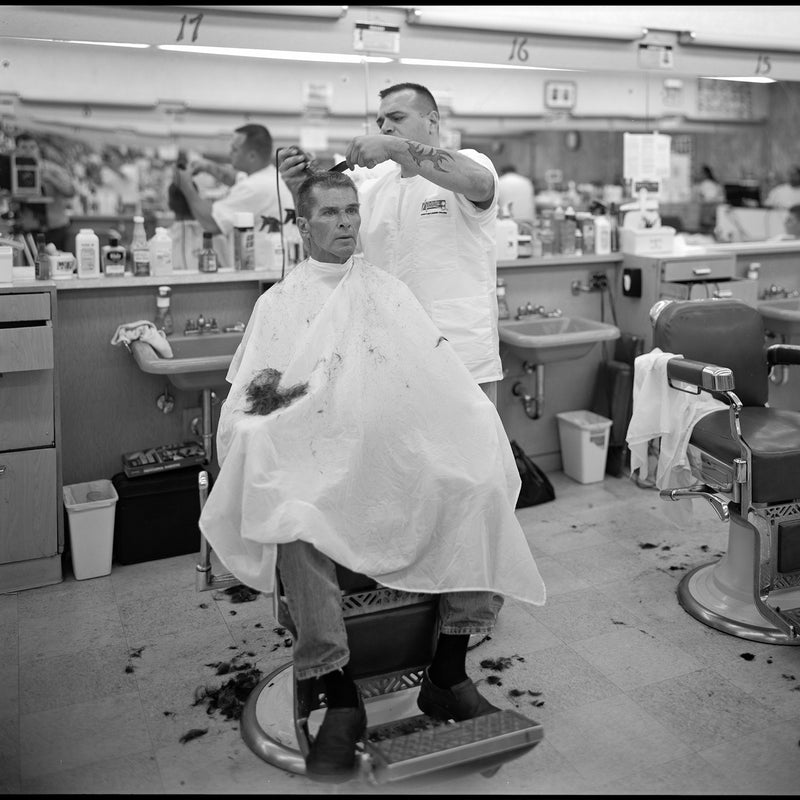

This story begins in January 2016. I was a digital landscape photographer, having been so since 2006, when I decided my 35mm film costs were getting too high and buying a DSLR would just be cheaper. I’d been doing fine art landscape work since about 2012 using a DSLR, and had become very comfortable doing so. I knew every Photoshop trick in the book and had thoroughly mastered things like focus stacking, exposure blending, luminosity masking, and sophisticated dodging and burning. But my images still left me feeling hollow, sick even.

Large format film slows you down dramatically. It forces you to care about every image in a way that we humans can’t seem to muster when using digital tools for some unbeknownst psychological reason.

There are a lot of photographers that inspire me, and I keep a constantly growing collection of photo books by the likes of David Muench, Eliot Porter, Philip Hyde, Galen Rowell, Ansel Adams, Nick Brandt, Michael Kenna and others. I think it’s healthy to know our heritage as photographers, and these artists have thoroughly mastered their craft. Introspectively looking at my own images, I found that while mine felt excessively “digital” or “artificial” and hollow, theirs felt deep and soulful.

So I began analysing their work and looking for commonalities, anything I could learn from, any pattern I could detect. They all shot quiet, contemplative scenes, or if they shot grand landscapes, they were exquisite and delicate, not gaudy and loud. Also, they all shot on film. Every last one of them. And of the landscape photographers whom I most admired and aspired to, those photographers all used large format view cameras. Now, I know the camera doesn’t make the image. A good editor can make an iPhone image look virtually indistinguishable from a medium format digital image. But… the tools you use influence and in some cases even dictate the way you work. Large format film slows you down dramatically. It forces you to care about every image in a way that we humans can’t seem to muster when using digital tools for some unbeknownst psychological reason. Additionally, you just can’t fake that classic, beautiful film aesthetic. So it was with these things in mind I decided to switch back to film, planning to end up on large format.

In January, I bought a Zenza Bronica ETR-Si 645 to get used to exposing medium format film, having every exposure cost money, and having a delay between capture and consumption. It worked, and I noticed an immediate improvement in the way I was working in the field and in the subjective aesthetic qualities of my images. I was happier and more relaxed in the field, and it showed in my images. Film photography was addicting, and I found wanted more resolution. I purchased a Mamiya RB67 6x7 camera with bellows focusing to get used to an even larger film plane and a slightly higher film cost, but therefore more attention paid to each image.

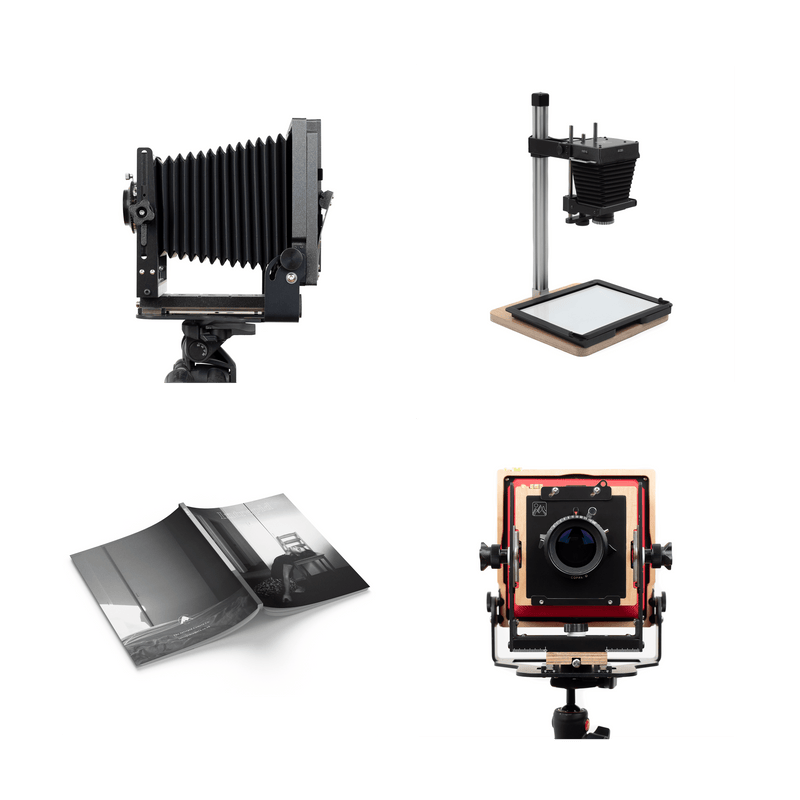

In July 2016, Intrepid announced that they had cameras available, and I placed my order within a few minutes of receiving the email. As my photography is primarily a passion, not a business, it was hard to justify the expense of some of the fancier large format cameras. Most of the places I do photography are located far in the wilderness backcountry, so I am always carrying my gear in a backpack on long and strenuous hikes. Carrying a heavy camera wasn’t something I would look forward to, so when I saw that the Intrepid was both affordable and the lightest 4x5 view camera in the world, it was a game changer for me and by far the best choice for getting into 4x5 film.

The icing on the cake was the minimalist design of the camera. As someone who greatly appreciates minimalist design and simplicity in product design, the Intrepid really stood out as by far the simplest 4x5 camera around, while retaining full functionality and still having an extensive range of movements and support for various backs, accessories and lenses.

In the first week of October, I received my Intrepid Camera, just the nick of time as at the end of that week I was scheduled to leave for my annual fall colour trip to California’s Eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains. My family was travelling with me, and we would be staying in Mammoth, California, right outside Devil’s Postpile National Monument.

Fortunately, my family loves the outdoors, and we didn’t waste any time getting outside and finding some fall colour. On one of the first days in the Sierra, we drove to the June Lake Loop and explored the area around Silver Lake, which was a gorgeous spot filled with vivid yellow Aspen trees surrounding deep blue alpine lakes and framed by silver mountains.

I made a few exposures on the Intrepid camera here, looking up into the Aspens from near ground level at a steep angle. The camera was easy to focus and I was able to use movements on the front standard to roll the depth of field plane onto the tree trunks to keep everything in sharp focus nicely. I metered the scene on my Pentax analogue spot meter and exposed 3 sheets of Kodak Ektar 100 colour negative film.

A day or so later, we drove my 4x4 up the dirt road all the way up into Lundy Canyon, which is home of the Lundy Lakes and several beaver ponds. I made an exposure from the side of the rough road on my Intrepid on Velvia 100, and some bystanders stopped to compliment the camera and ask about it. They had never seen a large format camera before, and were quite curious as to what it was and how it worked!On our way out of the canyon, I stopped to explore a stand of Aspens in soft light in the forest on the side of the road. The trees were in peak fall color, but the light was dim and flat, so I was concerned the image would not come out very good. However, I was extremely surprised and happy to find that the Fuji Velvia 100 rendered the scene incredibly well! It made the trees look almost 3-dimensional, and rendered the colors vividly. Velvia is like a magic bullet for soft scenes in overcast light, and the large format film preserved every detail in perfect clarity. I would love to make a huge print of this image!

The next day, we took the 4x4 again and drove into Lee Vining Canyon, which is a nice little rough dirt road that follows a meandering stream with some waterfalls along it, and lots of fall colour-laden Aspens, framed by massive pines. I found a nice little scene in a natural forest clearing along the side of the road, where two huge Jeffrey Pines framed a Spruce tree, with small gold-coloured Aspens growing all around.

In order to frame this scene, I needed to stand in the clearing just 15 or fewer feet from the trees. I wanted to include the first 50 feet of the tree trunks, in order to have the image framed by the first branches reaching down from above. To frame this scene with any other type of camera, you’d need to angle the camera up steeply at the trees, making them appear to converge in a triangle shape like this: /\. I’m sure you’re familiar with the effect.

However, when shooting large format film, we have an amazing trick up our sleeves which allows us to keep the camera perfectly level and simply move the lens up on the front standard using what’s known as a “vertical rise” movement. This reveals more of the scene that is above where the camera is ‘looking’ and therefore allows us to include more of the trees in a perfect vertical perspective, with no distortion. Because my 90mm f/8 Schneider-Kreuznach Super-Angulon lens is mounted in a recessed Linhof lens board, I am able to make extreme movements without any vignetting that could be caused by running into the edges of the image circle. This combination of generous movements on the Intrepid and the excellent coverage provided by a recessed lens board made this image possible.

My family had to head home on Wednesday, so I had the remainder of the week to myself to explore the area. On Wednesday morning I awoke before dawn and drove up to a beautiful overlook at over 10,000 feet elevation on an exposed mountain ridge to watch the sunrise alpenglow illuminate the Sierra, looking out across Devil’s Postpile National Monument to a series of mountains known as the minarets. I exposed sheets of both Kodak Ektar 100 and Fuji Velvia 100, and both came out great. I prefer the way the Velvia renders the scene with deep violet colours and rich contrast, so I chose to scan that one.

It is difficult not to notice how well the silent analogue elegance of a simple wooden camera fits with being in the wilderness

That evening, I made my way out to Mono Lake to explore some of my favorite “Sand Tufa” formations on the shores there. In the last light after the sun went down, the sky illuminated with a soft violet glow, and I made some exposures on Fuji Velvia 100 with my Intrepid camera. They came out great, and once again the Velvia rendered the scene beautifully!

The next morning, I arose well before dawn to drive out to a creek that is filled with aquamarine blue water that is steaming hot and riddled with mud pots and small geysers. The creek made for a gorgeous foreground with the alpenglow of the first light of dawn illuminating the Eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada range in the background. This image came out perfectly on Fuji Velvia 100, and the scan was truly incredible. In the full-resolution scan, I can even count the trees on a mountainside that is over 6 miles away from the camera! This is truly one of the delights of working with large format film. The color rendition, aesthetic beauty, and detail resolution are simply exquisite.

The simplicity of the Intrepid camera allowed me to stand back and focus on the scene without fiddling with complex camera controls. There was only one other photographer there, clacking away with a noisy little DSLR, with its beeping noises, flashing lights and flickering screen, fiddling away staring into computer menus while the beautiful light on the mountains began to fade. Certainly, I hold nothing whatsoever against digital photography or digital photographers (I was one until a year ago!), but it is difficult not to notice how well the silent analogue elegance of a simple wooden camera fits with being in the wilderness, in contrast to the digital distractions of the modern world. If you have not yet enjoyed this experience, it is well worthwhile to experience this peaceful simplicity for yourself.

Later, I decided to try my hand at finding a place to capture a sunset along the shores of Lundy Lake, so I drove out there again, this time in the afternoon, and scouted a place away from the ends of the lake which would be crowded by other photographers and fishermen. I was pleased to find a serene cove along the shore, strewn with massive granite boulders and lined with gorgeous golden Aspen trees adorned in the peak of fall colours. I made a couple of exposures on Fuji Velvia 100 at the opportune moment shortly after sunset when the light was at its best, one of which you see here.

As I hiked up through the forest hills back to my car, a herd of Mule Deer scattered through the underbrush, crashing through the bushes just a few feet from me. And with that, my Eastern Sierra autumn large format photography trip came to a close. The next morning, I woke up late, had some delicious coffee from an excellent cafe in Mammoth, and made the 6-hour drive back home.